FILE – A sign is displayed on May 27, 2021, at a memorial in Tacoma, Wash., where Manuel “Manny” Ellis died March 3, 2020, after he was restrained by police officers.

Police wrestle the unarmed Black man to the sidewalk. One officer pushes his face into the pavement as he pleads in vain: “Can’t breathe.”

Witnesses capture the scene at a dark intersection on their cellphones — one yells, “Hey! Stop! Oh my God, stop hitting him!” — and the medical examiner rules the man’s death a homicide.

The story evokes images of George Floyd begging for his life under the knee of a Minneapolis officer in May 2020. But this wasn’t Floyd.

This is the story of Manuel Ellis, who died, hogtied and handcuffed by three Tacoma officers, nearly three months before Floyd’s death would spark an international outcry against police brutality.

Get top local stories in San Diego delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC San Diego's News Headlines newsletter.

Ellis’ death, which coincided with the first U.S. outbreak of COVID-19 at a nursing home in Kirkland, Washington, became a touchstone for racial justice demonstrators locally but did not garner the attention of Floyd’s murder in front of a crowd in broad daylight.

Still, the trial of the officers charged in Ellis' case is another example of video footage of a violent arrest possibly playing a critical role in determining whether the police should be held accountable.

It’s also the first trial under a 5-year-old Washington state law designed to make it easier to prosecute police who wrongfully use deadly force. Opening statements are expected this week in a trial that could last more than two months.

Ellis, 33, was walking home with doughnuts from a 7-Eleven on the night of March 3, 2020, when he passed a patrol car stopped at a red light. Officers Matthew Collins and Christopher Burbank sat inside.

After what witnesses said appeared to be a brief conversation between Ellis and the officers, Burbank, in the passenger seat, threw open his door, knocking Ellis down. The officers, both white, tackled and punched Ellis, with one stunning him with a Taser as the other held him in a neck restraint.

A third officer, Timothy Rankine, arrived after Ellis was already handcuffed, face-down, and knelt on his upper back as Ellis pleaded for breath.

Police claimed Ellis had tried to open the door of another vehicle at the intersection, struck the window of their cruiser and swung his fists at them, but witnesses said they observed no such things.

The three civilian witnesses — a woman in one car, a man in another, and a pizza delivery driver in a third car — all said they never saw Ellis attempt to strike the officers, according to a probable cause statement filed by the Washington attorney general’s office, which is prosecuting the case.

Video, including cellphone footage taken by the witnesses and surveillance video from a doorbell camera nearby, variously showed Ellis raising his hands in an apparent gesture of surrender and addressing the officers as “sir” while telling them he can’t breathe. One officer is heard responding, “Shut the (expletive) up, man.”

“The police version of events has always been taken as the gospel truth,” said Philip Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

“And what these cases show us, especially when there’s video evidence, is that oftentimes the actual narratives of the police officers, whether in police reports, whether they’re testifying, are sometimes inconsistent with the video evidence," Stinson continued. "And that’s what gets closer scrutiny by the prosecutors and investigators.”

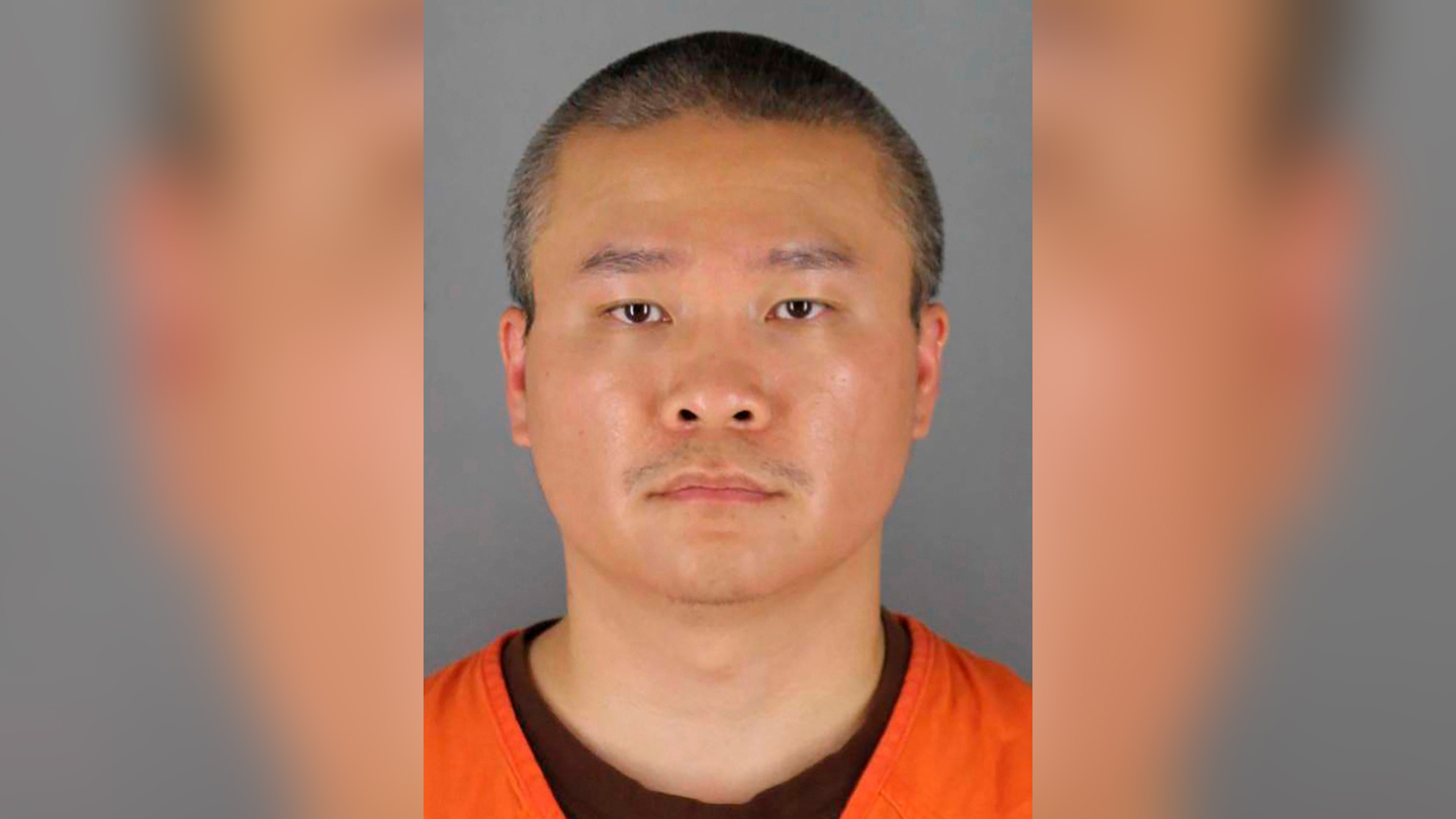

Collins and Burbank are each charged with second-degree murder. Rankine, who is Asian American, is charged with manslaughter.

They argue Ellis would not have died had he not taken methamphetamine and had underlying health issues. The Pierce County medical examiner determined Ellis’ cause of death was a lack of oxygen as a result of his restraint, with meth intoxication and an enlarged heart as complicating factors. But medical experts hired by the defense are expected to testify it was the meth that killed him.

The trial will feature the work of forensic analysts hired by prosecutors to examine audio and video from cell phones, a doorbell camera and 911 dispatch tapes to create “a comprehensive transcript of the incident.”

Collins' lawyer said the video only shows “a fraction” of what happened that night.

“While it may well have made it ‘easier’ to charge the officers, we are confident that the evidence presented in its entirety will show that Officer Collins is innocent of the charge he is facing, and the jury in this case will hold the State to its burden, and deliver a not guilty verdict," Dan Gerl, CEO of the Puget Law Group, told The Associated Press in an email.

The Ellis family said they hope the trial will be a turning point “in favor of truth and justice.”

“A police badge should not be seen as a license to commit human rights violations," his family said in a Sept. 18 press release. "Murder is not justified because the victim suffered from mental problems or substance abuse.”

How the encounter started and whether Ellis was violent toward the officers are critical points when trying to determine if the officers were justified in using force. In 2018, Washington voters approved a measure removing a longstanding requirement that prosecutors had to prove police acted with malice to charge them criminally for using deadly force. No other state had such a hurdle to charging officers.

One other officer has been charged since the law passed. Auburn police Officer Jeffrey Nelson was charged in the fatal shooting of Jesse Sarey in 2019 and is still awaiting trial.