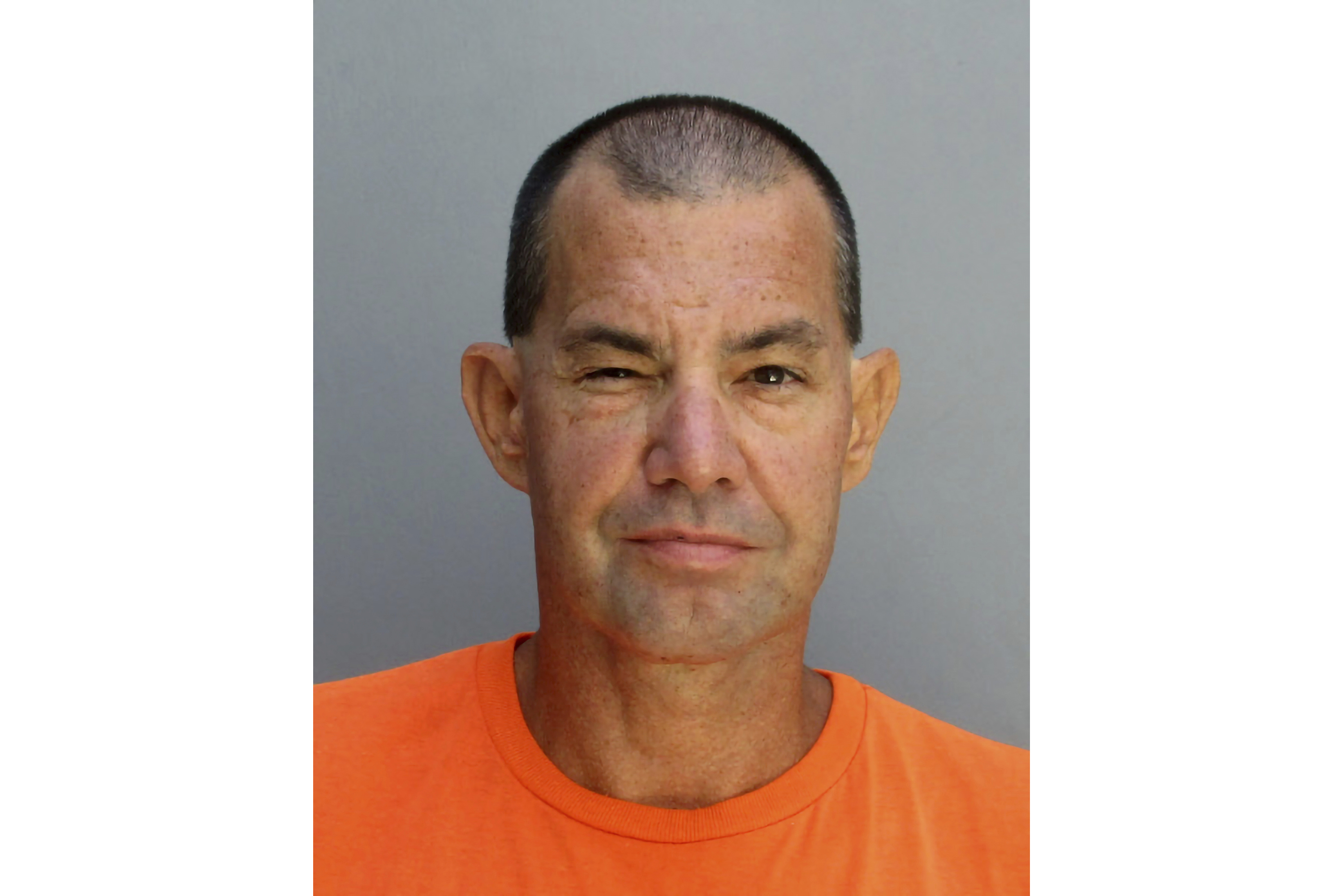

A parole board decided unanimously Wednesday that Susan Smith should remain in prison, despite her plea that God has forgiven her for infamously killing her two young sons 30 years ago by rolling her car into a South Carolina lake while they were strapped in their car seats.

It was the first parole hearing for Smith, 53, who is serving a life sentence after a jury convicted her of murder but decided to spare her the death penalty. She is eligible for a parole hearing every two years now that she has spent 30 years behind bars.

Smith made her case by video link from prison. She started by saying she was “very sorry,” then broke down in tears and bowed her head.

“I know what I did was horrible,” Smith said, pausing and then continuing with a wavering voice. “And I would give anything if I could go back and change it.”

Get top local stories in San Diego delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC San Diego's News Headlines newsletter.

In her final statements, Smith said God has forgiven her. “I ask that you show that same kind of mercy, as well,” she said.

Smith made international headlines in 1994 when she insisted for nine days that a Black carjacker drove away with her sons. Prosecutors have long argued that Smith killed 3-year-old Michael and 14-month-old Alex because she believed they were the reason the wealthy son of the owner of the business where she worked broke off their affair. Her attorneys blame her mental health.

A group of about 15 people urged against parole. They included her ex-husband and the father of the boys, David Smith; his family members; prosecutors; and law enforcement officials. Along with a few others, David Smith had a photo of Michael and Alex pinned to his suit jacket.

U.S. & World

He struggled to get out words at first, pausing several times to compose himself. He said he has never seen Susan Smith express remorse toward him. “She changed my life for the rest of my life that night,” he said.

“I’m asking that you please, deny her parole today, and hopefully in the future, but specifically today,” he said, adding that he plans to attend each parole hearing to make sure Michael and Alex aren’t forgotten.

A decision to grant parole requires a two-thirds vote of board members present, according to the state. Parole in South Carolina is granted only about 8% of the time and is less likely with an inmate’s first appearance before the board, in notorious cases, or when prosecutors and the families of victims are opposed.

Before Smith testified, she listened stoically to a statement from her attorney, Tommy Thomas. He called her situation one about “the dangers of untreated mental health.” He also noted she had no criminal history before her conviction, making her “low risk” to the public.

The board’s decision was the one David Smith had hoped for, Smith said in a news conference following the hearing. "In two more years, we’ll go through this again,” he said. “But at least I know, for now, she’ll still be behind bars.”

The family and prosecution had been “cautiously optimistic," former prosecutor Tommy Pope said, because Susan Smith has continually demonstrated that it’s “always been about Susan.”

A true-crime touchstone

Smith had claimed in October 1994 that she was carjacked late at night near the city of Union and that a Black man wearing a toboggan hat drove away with her sons. The claims by Smith, who is white, played into a centuries-old racist trope of Black men being a danger to white women and stoked concerns about crime that were prevalent in 1990s America and remain so today.

For nine days, Smith made numerous and sometimes tearful pleas asking that Michael and Alex be returned safely. The whole time, the boys were in Smith’s car at the bottom of nearby John D. Long Lake, authorities said.

Investigators said Smith’s story didn’t add up. Carjackers usually just want a vehicle, so investigators asked why they would let Smith out but not her kids. The traffic light where Smith said she had stopped when her car was taken would only be red if another car was waiting to cross, and Smith said no other cars were around. Other bits and pieces of the story did not make sense.

Smith ultimately confessed to letting her car roll down a boat ramp and into the lake. A re-creation by investigators showed it took six minutes for the Mazda to dip below the surface, while cameras inside the vehicle showed water pouring in through the vents and steadily rising. The boys’ bodies were found dangling upside-down in their car seats, one tiny hand pressed against a window.

The 1995 trial of the young mother became a national sensation and a true-crime touchstone.

Smith’s lawyers said she was remorseful, was suffering a mental breakdown and intended to die alongside her children but left the car at the last moment. They were successful at sparing her life.

“I just felt strongly that had the Black man with the toboggan committed the crime, people would expect the death penalty,” Pope said at Wednesday’s hearing. “If David Smith had committed the crime, people would have expected the death penalty.”

Pain to family, state and nation

The parole board asked Smith about the law enforcement resources used to try to locate her children. In reply, she told the board she was “just scared” and “didn’t know how to tell them.”

Smith’s crime traumatized not only her family, prosecutor Kevin Brackett said, but also people in South Carolina and around the country who “fixated” on this “global sensation.” Her allegation that a Black man kidnapped her children also led to other Black men being wrongfully pulled over as police searched for a “fictitious man,” he said.

From prison, Smith can make phone calls and answer text messages, many from journalists and interested men. Those messages and phone calls were released under South Carolina’s open records act, something Smith didn’t initially realize could happen. She said the invasion of her privacy upset her, along with the public revelation that she was juggling conversations about the future with several men.

Some men know why she is famous. Others are more coy. One told her he was going to use the dates of her birthday and those of her dead sons when he played the Powerball lottery. Others chatted about their lives and sports. Many promised her a home on the outside and a happy life.

Smith also had sex with guards. And she violated prison policies by giving out contact information for friends, family members and her ex-husband to a documentary producer who discussed paying her for her help, according to Pope, the former prosecutor.