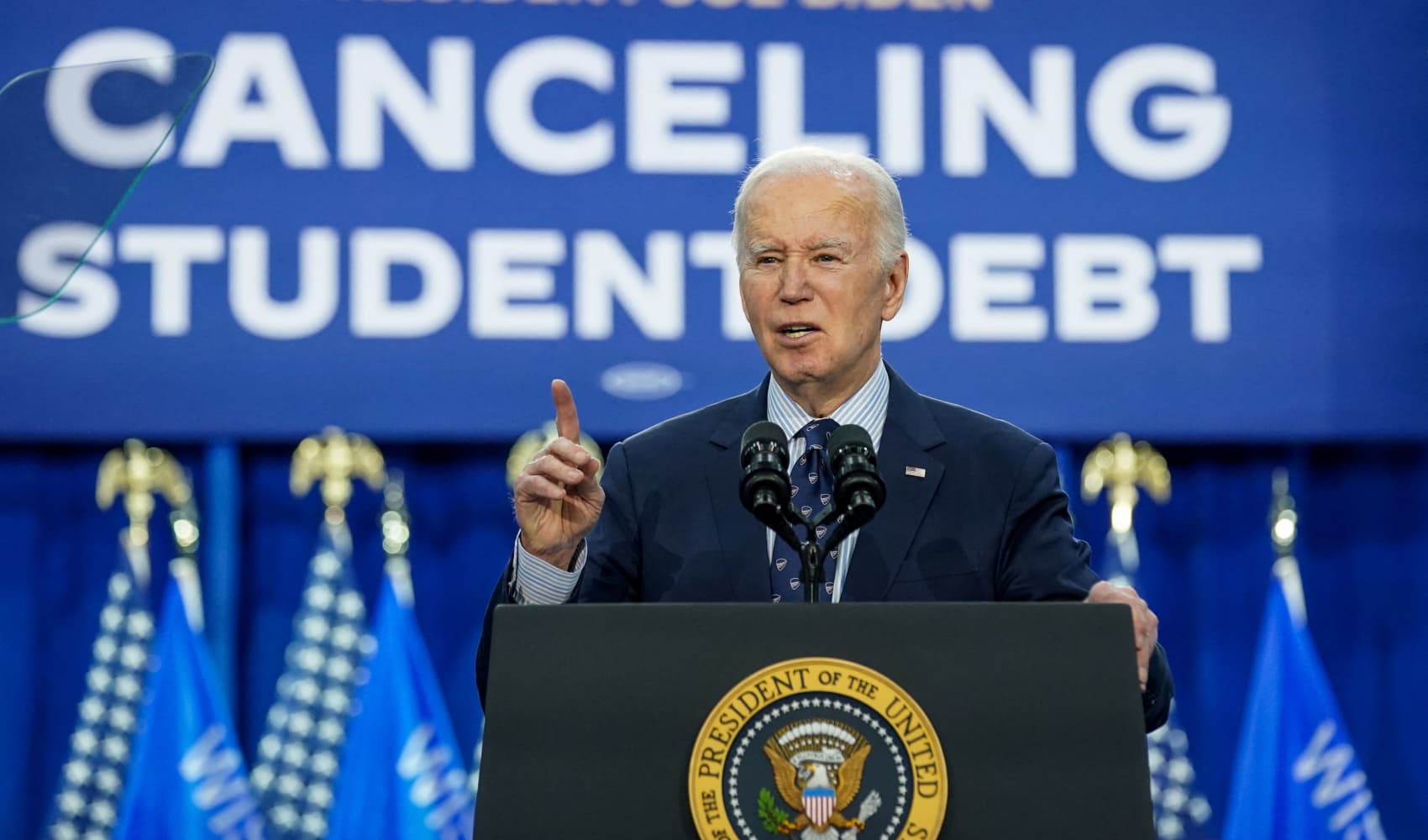

Rarely a day goes without President Joe Biden mentioning insulin prices.

He promotes a $35 price cap for the medication for Americans on Medicare — in White House speeches, campaign stops and even at non-health care events around the country. His reelection team has flooded swing-state airwaves with ads mentioning it, in English and Spanish.

All that would seemingly add up to a sweeping political and economic impact. The reality is more complicated.

As his campaign tries to emphasize what it sees as an advantage over presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump, Biden often overstates what those people who are eligible for the price cap once paid for insulin. It’s also not clear whether the number of Americans being helped will be enough to help sway November’s election, even in the most closely contested states that could come down to a few thousand votes.

Get top local stories in San Diego delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC San Diego's News Headlines newsletter.

“It is about political signaling in a campaign much more than it is about demonstrating for people that they benefit from the insulin cap,” said Drew Altman, president and CEO of KFF, a nonprofit that researches health care issues. “It is a way to make concrete the fact that you are the health care candidate.”

Many who are benefiting from the price cap were already getting insulin at reduced prices, were already Biden supporters, or both. Others who need reduced-price insulin, meanwhile, cannot get it because they do not have Medicare or private health insurance.

Biden’s campaign is emphasizing the president's successful efforts to reduce insulin prices and contrasting that with Trump, who first ran for president promising to lower drug prices but took limited action in office.

“It’s a powerful and tangible contrast,” said Biden campaign spokesman Charles Lutvak. “And it’s one we are campaigning on early, aggressively, and across our coalition.”

US & World

Roughly 8.4 million people in the United States control their blood sugar levels with insulin, and more than 1 million have Type 1 diabetes and could die without regular access to it. The White House says nearly 4 million older people qualify for the new, lower price.

The price cap for Medicare recipients was part of the Inflation Reduction Act, which originally sought to cap insulin at $35 for all those with health insurance. When it passed in 2022, it was scaled back by congressional Republicans to apply only to older adults.

The Biden administration has also announced agreements with drugmakers Sanofi, Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly, to cap insulin co-payments at $35 for those with private insurance. They account for more than 90% of the U.S. insulin market.

But Biden says constantly that many people used to pay up to $400 monthly, which is an overstatement. A Department of Health and Human Services study released in December 2022 found that people with diabetes who were enrolled in Medicare or had private insurance paid an average of $452 annually, not monthly.

The high prices the president cites mostly affected people without health insurance. But the rates of the uninsured have fallen to record lows because of the Obama administration’s signature health care law and the Biden White House’s aggressive efforts to ensure those eligible to enroll are doing so more frequently.

So, in effect, one of the administration’s policy initiatives is undermining the economic argument for another.

That effort has not reached everyone, though.

Yanet Martinez who lives in Phoenix and supports Biden. She does not work or have health insurance, but gets insulin for around $16 per month thanks to steep discounts at her local clinic.

The lower prices only apply if her husband, a landscaper, does not make enough to exceed the monthly income limit. If he does, her insulin can jump to $500-plus, she said.

“I’ve heard people talk about the price of insulin going down. I’ve not seen it,” said Martinez, 42. “It should be uniform. There are a lot of people who don’t have any way to afford it and it makes things very difficult.”

Sen. Raphael Warnock, D-Ga., is sponsoring bipartisan legislation to make the $35 insulin cap universal, even for people without health insurance. In the meantime, he said, what's been accomplished with Medicare recipients and drugmakers agreeing to reduce their prices is "literally saving lives and saving people money.”

“This is good policy because it centers the people rather than the politics," Warnock said. He said that as he travels Georgia, a pivotal swing state in November, people say “thank you for doing this for me, or for someone in my family.”

That includes people like Tommy Marshall, a 56-year-old financial services consultant in Atlanta, who has health insurance. He was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes at age 45 and injects fast-acting insulin several times daily. He paid about $250 for four weeks to eight weeks worth of medication last November, but saw the price fall by half in February, after Novo Nordisk agreed to cut prices.

“If I was his political consultant, I’d be telling (Biden) to talk about it constantly," said Marshall, a lifelong Democrat and longtime public advocate for cutting insulin prices, including for the advocacy group Protect Our Care Georgia.

Marshall said the price caps “have meaningful emotional resonance” and could sway a close election but also conceded, “You’re talking about 18- to 65-year-olds. I can just imagine there’s probably two or three other issues that are in front of this one.”

“Maybe someone sort of on-the-fence, he added “this could maybe sway them.”

Geoff Garin, a pollster for Biden's reelection campaign, said the insulin cap is one of the president's highest performing issues. He said the data was “clear, consistent and overwhelming.”

Rich Fiesta, executive director of the Alliance for Retired Americans, which has endorsed Biden, called the insulin cap a strong issue for the president among older voters.

“For the persuadables — and there are some still out there, believe it or not — drug costs are a very important factor,” said Fiesta, whose group has 4.4-million members and advocates for health and economic security for older people.

In the News

Trump's campaign did not respond to questions. But Theo Merkel, senior fellow at the conservative Paragon Health Institute, countered that the insulin price cut an example of "policies written to fit the talking points other than the other way around.”

Merkel, who was a Trump White House adviser on health policy, said manufacturers that have long made insulin prefer caps on how much the insured pay because it gives them more leverage to secure higher prices from insurance companies.

The president's approval ratings on health care are among his highest on a range of issues, but still only 42% of U.S. adults approve of Biden’s handling of health care while 55% disapprove, according to a February poll from The Associated Press and the NORC Center for Public Affairs Research.

KFF found in its own poll in December that that 59% of U.S. adults trust the Democratic Party to do a better job addressing health care affordability issues compared to 39% for Republicans, even if only 26% of respondents in the same poll said they knew about the insulin price cap.

“In political terms, the Democrats and Biden have an advantage on health care," Altman said. “They're pressing it.”