Last year, SDPD only hired about 120 new officers despite receiving more than 3,000 applications. NBC 7’s Wendy Fry heard from an SDPD Lieutenant and the president of the Police Officers Association about the different challenges the department is facing.

Even after ramping up recruiting efforts and bumping compensation, the San Diego Police Department (SDPD) continues to struggle with staffing shortfalls.

NBC 7 has learned that among more than 4,000 applications SDPD receives each year on average, only about 100 officers are hired annually. Very few applicants make the cut during the long and intense hiring process.

About 200 budgeted positions remain vacant of the department's 2,000 sworn police officer positions.

But, the department is losing about 150 officers a year, while only bringing on 90 to 120 officers annually.

"Clearly, it's pay and benefits," said Brian Marvel, the president of the Police Officer's Association.

Marvel said the chronic police officer shortage could be addressed by making pay more comparable with other nearby agencies.

But there is no shortage of applicants.

Local

Out of thousands that apply each year, only a handful, about four percent of applicants become new hires with the city to attend the Academy for SDPD.

That pool of applicants is dramatically dropping though.

"That's a huge concern for us because in order for us to fill 200 recruits in the Academy, we need 5,000 candidates," Marvel said.

In Fiscal Year 2013, 4,439 applicants took the first step in applying to become San Diego police officers, which is a written test.

An average of four percent of applicants make it through the hiring process to the first day of the Academy. Of that, only one in four make it through the Academy and field training process, according to the police union.

Using those averages, only 44 officers would have ended up joining the police force from the 4,439 applicants in 2013.

Applicants endure a tough process lasting months that includes the written examination, an extensive background check, a lie detector test, several rounds of interviews, and they complete a timed obstacle course.

"It's not about how tough it is," said Lt. Michael Swanson in charge of recruiting. "It's about getting the 'best of the best' to be San Diego police and out there working in the community."

Of the select handful that make it to the Academy, there are seven months of training before an officer gets his or her badge. Then, the trainee spends five months with a field training officer.

"You have to remember, we're empowering people to make some pretty heavy decisions within the community, up to and including lethal force, if necessary," Swanson said. "So, we only want to have the 'best of the best' with that kind of authority."

The department is also facing shortages of field training officers.

City leaders had hoped an increase in benefits last year would reduce departures from the department, but Chief Shelley Zimmerman said the improved compensation package has had little effect on officer retention.

Marvel said six officers are leaving in the next two weeks. One new police officer leaving for Riverside Police Department will be increasing his pay by $9 an hour, or about $90 a day, Marvel said.

Zimmerman told City Council members in March that police are leaving for a variety of reasons, including pay, morale, workload and “the climate of what’s going on, the national dialog of what’s going on.”

“Many (news) stories across the country are painting police in a negative light,” Zimmerman said.

Add to that being exposed to tragedy, stress and tense moments on the job, and it becomes even more clear why the department conducts such a rigorous screening and hiring process, according to officers in recruitment.

"This is to make sure that we get the absolute best, qualified applicants for the City of San Diego," Swanson said.

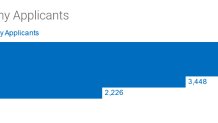

Between fiscal years 2015 and 2016, there was a more than 25 percent drop in the number of applicants.

Little data exists to explain the significant drop in number of applicants between 2015 and 2016.

In July 2016, a veteran uniformed San Diego police officer was killed in the line of duty, and another officer was seriously injured. San Diego Police Officer Jonathan De Guzman was shot multiple times, at point-blank range in his patrol vehicle, by a Shelltown gang member. Prosecutors said De Guzman never had a chance to even raise his service weapon.

The 2014 officer-involved shooting death of a black teen in the St. Louis suburb of Ferguson thrust police into the national spotlight, and increased scrunity of police officers' interactions with minorities.

Since then, high-profile incidents in Baltimore, Chicago, Baton Rouge and even El Cajon, which is not served by the San Diego Police Department, but within 15 miles of its jurisdiction, have spurred public protests and been the subject of many media reports on divides between minority communities and the police that serve those communities.

A recent study by the Pew Research Center found more than eight in 10 officers said police work is harder today as a result of those high-profile and deadly encounters.

More than 75 percent of 8,000 officers surveyed said they are reluctant to use force when necessary as a result of the high-profile incidents and nearly 72 percent said they are less likely to stop and question people who seem suspicious as a result of increased public scrunity of police.

Whether the so-called "Ferguson effect" has impacted crime rates or officer retention or how many applicants the police department receives each year remains unclear.

The survey suggest the impact has been severe on the morale of rank-and-file police officers.

"Within America's police and sheriff's departments ... the ramifications of these deadly encounters have been less visible than the public protests, but no less profound," according to the Pew Report.