A case of polio was diagnosed in an unvaccinated, healthy 20-year-old man in Rockland County, New York in June, causing partial paralysis and catching the attention of local health officials.

The virus was then discovered in wastewater in at least four New York counties. Genetic samples of wastewater in London and Israel showed the same virus was also found there. New York state health officials ramped up efforts to get the public immunized with the polio vaccine that was first invented by the late Dr. Jonas Salk.

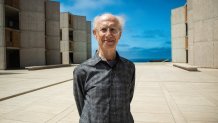

Dr. Peter Salk of La Jolla, who is the eldest of Salk's three sons, said his father "would have a lot to say" about these recent developments if he were alive today. He explained why in an interview with NBC 7 at the renowned Salk Institute in La Jolla, the famed research center that his father built and opened in the 1960s.

He would have a lot to say today because he was upset when the live oral vaccine was first introduced.

Peter Salk, M.D., Jonas Salk's son

Get top local stories in San Diego delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC San Diego's News Headlines newsletter.

New York state health officials said the diagnosed polio patient may have contracted it from a person from overseas who was vaccinated with the oral vaccine. The oral vaccine contains a weakened version of the live virus, which in rare cases could mutate and spread. It has not been used in the U.S since 2000.

In contrast, the Salk vaccine is injected and contains the killed virus.

Salk said his father "was upset when the live oral vaccine was first introduced... He thought it would be dangerous."

The polio virus is rare in the U.S. and despite the huge effort to vaccinate against it, the polio virus has never been completely eradicated throughout the world, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Local

Until that happens, Salk said, "we're still going to always be at risk, that a virus will travel with somebody on an airplane and be brought back."

We're still going to always be at risk that a virus will travel with somebody on an airplane and be brought back.

Peter Salk, M.D., Jonas Salk's son

Salk called the New York case a "wake-up call" to get vaccinated against polio, a disease that became a pandemic during the late 40s to early 50s.

Salk recalled with vivid memory how his father tested the polio vaccine on himself, his wife and his three young sons in 1953. Peter Salk was 9 at the time, his brother Darrell was 6 and Jonathan was almost 3.

Understandably, none of the three youngsters liked shots. But Salk said even though they didn't fully appreciate the significance of the polio pandemic, he said they "did have a sense that what our father was doing was something important. We had visited him in his laboratory… We knew there was something big that was afoot."

We knew there was something big that was afoot.

Peter Salk, M.D.

The Salk polio vaccine was licensed in 1955.

Salk and his two brothers followed in their father's footsteps with illustrious careers in medicine. Darrell is a pediatric geneticist, Jonathan is a psychiatrist and Peter is an infectious disease expert.

As Salk walks along the iconic "River of Life" water feature at the center of the Salk Institute that bears his father's name, he remarks, "this is just an unbelievable place."

Salk said he and his brothers are determined to carry on his father's legacy, which they say is the core of the Salk Institute -- to find answers and create a hopeful environment through collaborative research.

...full cooperation and support of one another.

Peter Salk, M.D.

"We have so many problems confronting us in the world and we really need to create a situation where we're relating in an optimal fashion with full cooperation and support of one another," Salk said.

So far there are no reports of cases of the poliovirus in California.

The California Department of Public Health (CDPH) says it is not currently monitoring wastewater samples for polio but is working with academic partners and the CDC to see if wastewater testing for poliovirus can be integrated for public health monitoring in California.