Amy Allen's journey to repay her student loan is a lesson in missteps mixed with good intentions.

Allen went to the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) for her undergraduate degree and San Diego State University (SDSU) for her master's. She graduated in 1999 with a student loan debt totaling $120,517.

Now, Allen’s loan balance is more than $145,000, even though she has repaid more than $80,000.

"That's the part to me that feels very Kafkaesque,” Allen said. “How did the numbers add up? Is there something I'm missing?"

One in ten people default on their student loan, according to the U.S. Department of Education. When a borrower defaults, their wages can be garnished, tax refunds seized, and/or their credit severely damaged.

Allen experienced some of those consequences.

She said she originally took advantage of a six-month grace period before she started to repay her student loan, but her loan accrued interest during that six month period.

Local

Experts say borrowers should always check the details of their loan and if you are able, pay the interest during the grace period, so your loan amount does not increase.

Allen started paying an estimated $600 a month on a so-called “graduated loan.” The monthly payments increased over time, on the assumption that the borrower’s income would also increase year-after-year.

Allen's loan payments jumped to an estimated $700 a month and eventually increased to $900 monthly, making it difficult for her to continue to pay.

"I couldn't see any way out of it,” Allen recalled. “I was like how am I going to repay this for basically the rest of my life?"

Allen filed for forbearance, which gives a borrower a respite from monthly payments. But interest on the loan continues to grow, adding to the total amount due.

When Allen resumed her payments, she was actually paying interest on the interest, a phenomenon known as “interest capitalization.”

"I paid $900 a month for eight years,” Allen said. “But the balance really wasn't going down, despite paying that much per month."

Feeling discouraged, Allen stopped paying on her loan for five months. If she withheld payments for four more months, her loan would go into default. So she hired an attorney who promised to enroll her in a Public Service Loan Forgiveness Program.

As a teacher working for a nonprofit organization, Allen’s attorney said she would qualify for loan forgiveness. If accepted, she would resume making payments for ten more years, at which time the entire debt would be forgiven.

While waiting for word on her application, the prospect of loan default loomed.

She said she asked her attorney if she should start paying again, but while waiting for that advice, her loan went into default.

"I should have just made the payments because, in retrospect, it cost me far more money not to make them, because they charge a 16% fee for defaulting [on the total amount of your loan]."

UCSD's Director of Financial Aid and Student Scholarships Vonda Garcia said, "The key is you can't let yourself go into default."

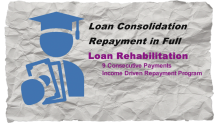

Garcia said there are loan servicers who can work with borrowers to help reduce their monthly payment by getting them into one of several income-driven repayment plans, which are based on a borrower's discretionary income.

"You have to keep in contact with the loan servicer and communicate with them what your situation is," she told NBC 7 Investigates.

Garcia said taking advantage of those repayment plans will increase the amount of the loan because interest will grow, but she says it is better than going into default.

"Once you start missing payments that's when things get much more difficult to get out of the situation," she added.

Difficult but not impossible. Borrowers who have defaulted on their loans have a one-time opportunity to rehabilitate their loans.

To rehabilitate her loan, Allen made nine consecutive payments on her loan and then got into an income-driven repayment plan. Now, she pays $1,000 a month.

"I feel good, I've addressed it, and I understand it, and I'm not avoiding it. That part of it does feel good, but when I think of 30 years of paying that amount of money...I will pay a number of times over the amount of my original loan, and that does not feel right when I am contributing to society."

Allen's advice: Keep paying your loan.

"Don't ignore it, I understand the propensity to do that because I did it, but it makes it worse for you. If you avoid paying your student loan, your situation is not going to improve."

She also said you do not need a lawyer to help you navigate what she acknowledges can be a complicated system.

"You can do it yourself if you're willing to learn, but it is complicated,” she said.

Allen spent last summer researching why she did not get accepted into the federal loan forgiveness service program. She discovered she had the wrong type of loan, a fact she claims her attorney failed to recognize.

After securing the type of loan she needed, Allen reapplied for the loan forgiveness program. She was recently accepted. If all goes well, instead of paying $1,000 monthly for 30 years, she will pay that amount for ten years. As long as she continues to teach at a nonprofit institution, her loan will then be forgiven.

"I recognize I did take out this money, and I do need to pay it back. I don't think it's someone else's responsibility, and so in that sense, I want to do the right thing. I want to pay the loans but I want to be done in ten years, so I can at least think of retirement at a normal age."