California may be reopening Tuesday, but the race against new coronavirus variants is one health workers are still waging every day. That’s where one extremely special volunteer comes in, reports NBC 7’s Alexis Rivas.

California may be reopening Tuesday, but the race against new coronavirus variants is one health workers are still waging every day. That’s where one extremely special volunteer comes in.

NBC 7 caught up with one worker we first met months back, and what we found isn’t just making a positive difference in the fight against COVID right now – local health leaders think it has the potential to change the way we approach health inequalities in the future.

San Diego grandmother Felicia House hits the streets every day on foot, going up to complete strangers, answering questions about – and hopefully – encouraging people to get the vaccine.

Not everyone is cut out for this but it’s hard to ignore House. She wasn’t always an advocate for the vaccine.

Get top local stories in San Diego delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC San Diego's News Headlines newsletter.

“I’m just going to be honest,” explained House. “I wasn’t going to get vaccinated either. But I wanted to learn.”

June 15 Reopening

Like for many Black Americans, that hesitancy has been passed down over generations.

“My grandmother told me, 'Don’t ever trust,' you know, ‘Don’t ever trust no white person coming up to you talking about take this medicine!’ I’m from the South. And I believed her," House said.

But that belief was challenged when House’s sister caught COVID-19 and, like so many others, died alone.

“Because I’m a Christian I know I will see her again,” House said. “I know the goodness of the Lord. So I’m not -- that’s not the hard part. The hard part is being separated from her. Not being able to hold her hand. Not being able to say it’s going to be OK. Some nurse has got to be the one to do that, and we should’ve been the ones to do that.”

House feels emphatically that her sister’s death, like the deaths of 600,000 Americans, was preventable.

“I don’t want anybody to have to go through that,” House said.

So House turned that anger and grief into action.

“When I lost my sister and I heard all of the lies being told, that’s when I got serious about COVID," she explained.

House “got serious” by getting involved with the Multicultural Health Foundation.

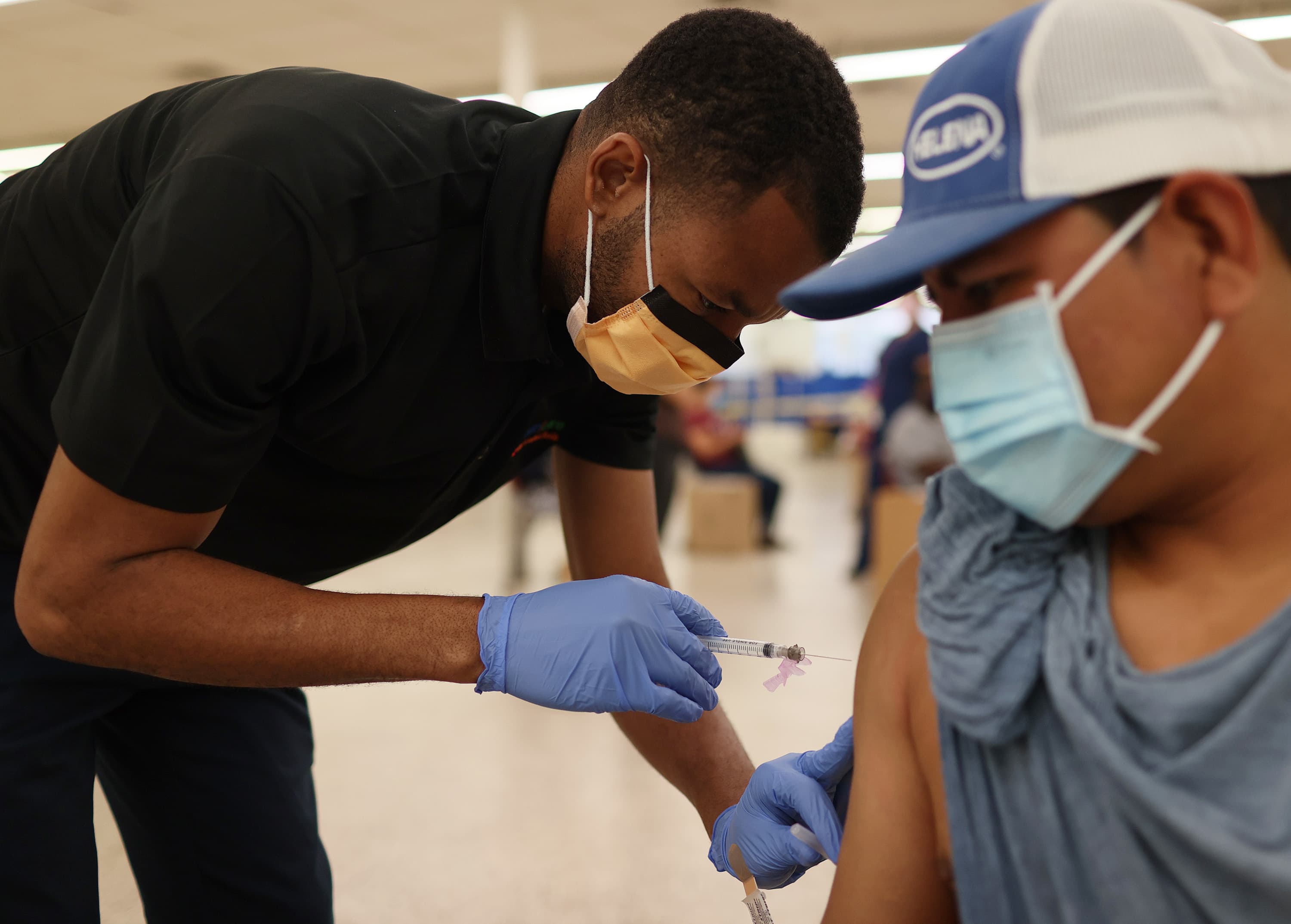

House is a community health worker: people on the ground having one-on-one conversations about the vaccine. It’s just one of several grassroots minority-focused programs the MHF launched during the pandemic – an effort from the county to ensure some minority-heavy neighborhoods don’t fall through the cracks.

“So to me that’s the silver lining,” said Dr. Rodney Hood, the president of the MHF. “It has uncovered inequities that we knew were already there.”

Hood said community health workers like House are uncovering much more than just a vaccination status. They’re learning about other inequities like the disproportionate rates of hypertension, lung cancer and diabetes impacting the Black community.

Hood said community health workers have already helped connect people with health services, and that’s already resulted in significant drops in cholesterol for some patients - patients who otherwise likely wouldn’t have sought treatment.

“It makes me feel that we’re doing something,” Hood said. “It certainly makes me feel like the effort that we are doing is really making a difference.”

Now Hood hopes the county turns what started as an emergency grant into a permanent program.

“I have the bug now,” House said.

And she doesn’t plan to slow down anytime soon. She's working to end the pandemic and keeping an eye on ending medical inequity in the years to come, one chat with a stranger at a time.

“This is something that can be turned around,” House said. “It really, really can. I’ve seen it happen. I’ve seen it happen.”