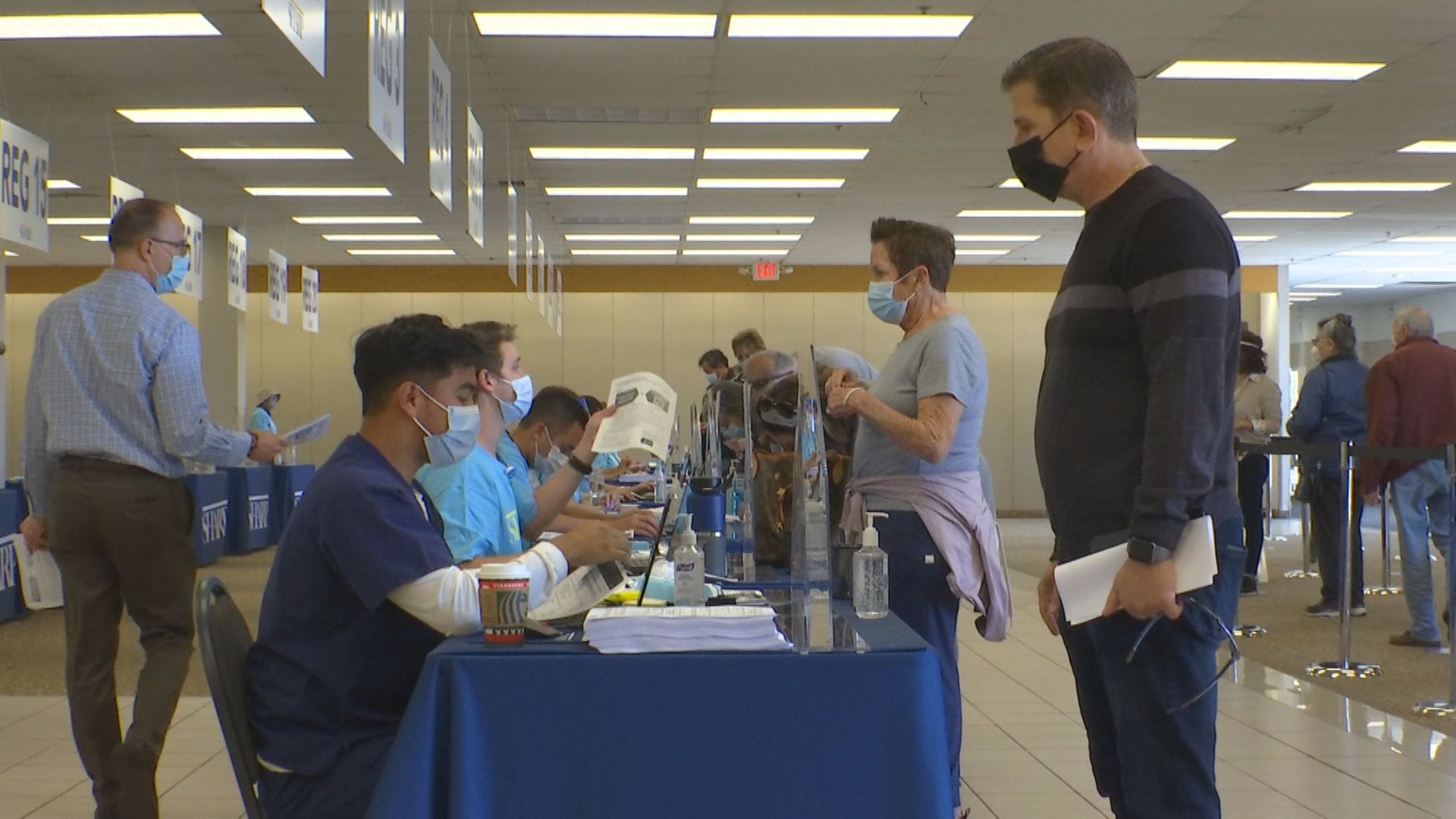

As the light at the end of the pandemic tunnel begins to come into focus, a hard fact remains; the Black and African-American population in this country accounts for some of the lowest inoculation rates nationwide and in San Diego County.

That’s why leaders across San Diego County have been trying to figure out how to convince Black fellow community members that the COVID-19 vaccines are safe, despite centuries of racism and distrust in the federal government.

Figures released this week by San Diego County health department officials reveal only 2% of vaccinations administered have gone to Black or African-American residents compared to 47.5% of vaccinations administered to whites. The Black or African-American demographic makes up 5% of San Diego County's population, according to 2019 Census figures.

Adding pressure to the situation is that the Black community has a greater risk of severe disease and death brought on by the effects of COVID-19, making it even more critical for full vaccine protection.

Get top local stories in San Diego delivered to you every morning. >Sign up for NBC San Diego's News Headlines newsletter.

“If a Black person ends up in the hospital with COVID-19, they're three times more likely to die than their counterparts.”

- Felicia House, San Diego Community Health Worker

These points and more have sparked a call to action by the Multicultural Health Foundation in San Diego -- a race against time that could mean life or death for their community.

Historical Roots of Distrust Can’t Be Pulled Overnight

Even though Felicia House is a Community Health Worker with the Multicultural Health Foundation, she admits she too was skeptical at first when she heard the news of the COVID-19 vaccines. What she heard from the top levels of government down to local officials raised red flags and post-traumatic stress for her community.

“We have good reason to be afraid,” House said. “When we hear something like ‘Oh, it's Warp Speed,’ the first thing that hits our mind is ‘Really? Well, we're just going to let you warp on out of here.”

Stories of the U.S. government performing medical experiments on their ancestors were handed down as warnings, generation to generation, said House.

“This is a very long historical phenomenon, and we are a culture that is what we call oral-based, so we tell stories to one another, and our elders tell us stories, and those are the best resources as a community that we have had and still do have,” House said.

Researchers concluded that in 1946, the U.S. government “immorally, unethically and possibly illegally” engaged in research experiments on more than 5,000 uninformed and unconsenting Guatemalan people. The National Center for Biotechnology Information found officials “intentionally infected” participants with bacteria that cause sexually transmitted diseases.

Then, there was the infamous and unethical “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis.”

It was not a study.

Instead, it was a non-therapeutic experiment carried out from 1932 to 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Service and Centers for Disease Control.

The subjects of the experiment included 600 Black men who were given unreliable information on the purpose of the experiment, nor were they informed on the debilitating and life-threatening consequences of the treatments they were to receive, according to the findings of a federal Advisory Panel formed to investigate the matter in 1973.

Half of the men enrolled in the study did not have syphilis but were infected with it, and doctors withheld treatments for the disease.

The findings concluded that there was no evidence that “informed consent was gained from the human participants in this study. Such consent would and should have included knowledge of the risk of human life for the involved parties and information regarding possible infections of innocent, nonparticipating parties such as friends and relatives.”

That example and more are why Felica House and other Black leaders have an uphill climb when trying to convince their community to take the CDC’s word on COVID-19.

“Not to say that the elders who told us stories are not valid, they are,” House said. “It has saved us many, many generations over but with this case, for this virus, it is important that we look at the facts to overcome the fear.”

Three Types of Vaccine Hesitancy

Rodney Hood, Ph.D., has heard the fears from his patients time and time again. As a local physician and the Board President of the Multicultural Health Foundation, these concerns and the realities of health disparities, in general, are not new.

Back in January, the San Diego County Board of Supervisors declared “racism a public health crisis,” a fact that Hood said the Black community recognized more than 50 years ago.

“What we mean by structural racism isn't the individuals themselves saying, ‘I'm going to do something negative with that patient,’” Hood explained. “But the system of infrastructure causing what I call ‘racialized poverty.’”

Even though these facts aren’t new, the systemic problems have been exposed clearly during the pandemic, Hood said.

“The reason why we have excess health disparities in this area, especially for African-Americans, is really historic, and it didn't begin with Tuskegee,” Hood explained. “It’s been decades of ethnohistoric discrimination and racism towards Blacks and Hispanics.”

Hood’s fears for his community’s safety come from the data behind COVID-19 infections and the effect it’s having on his neighbors.

“When the pandemic hit, if Blacks got COVID, they were more at risk to this severe disease and death,” Hood explained, saying it comes down to comorbidities or the presence of two or more diseases in a person at one time. “If you have one comorbidity, your risk is high. If you have multiple comorbidities, it is even higher.”

Hood said those comorbidities include increased hypertension, diabetes, and asthma -- health issues that have already plagued Black and Hispanic communities for decades.

“That's why you see African Americans dying at a greater rate [from COVID-19] because they have higher morbidity,” Hood said.

Hood himself, a member of both the county and state's task force on COVID 19, said he wasn’t convinced at first of the vaccine’s efficacy, but he concluded that it was safe once he did the research.

Through seeing patients, Hood has identified three types of vaccine hesitancy in San Diego’s Black community and nationwide: hesitancies over a lack of information, hesitancies based on distrust, and hesitancies coming from a place of “holistic resistance.”

There are different approaches to each type, he explained.

“Those that have a lack of information, just getting them that information and data they'll be convinced,” Hood said. “Those that historically distrust the system… to get to that population, you have to give them data and information, and it needs to come from a trusted source. Somebody who looks like them, and who can identify with them.”

And for those who are entirely resistant to the idea of getting vaccinated, Hood said, “Our approach is we still love them, and we only need to get 70 to 80 percent [of the population vaccinated.]”

Other Leaders Still Not Convinced, Will Not Take Vaccine

Despite the significant health risks for the Black community members, some leaders are still not convinced the vaccine is ready to go.

Leaders have credited Student Minister Abdul Waliullah “Hugh” Muhammad and his nonprofit “I Am My Brother’s Keeper” as a strong ally for the Black and African-American community during the pandemic.

The nonprofit that Muhammad leads as CEO has organized food drives for those who found themselves out of work, education outreach on safety guidelines during every stage of the pandemic, and creating a “super pantry” of food for southeast San Diego.

Muhammad said the systemic problem of food insecurities -- or neighborhoods lacking access to healthy and affordable food options -- is one he’s fought hard against while the virus has ravaged through every sector of society and economic norms.

Muhammad -- along with Doctor Hood and other community leaders -- sits on several local task forces designed to ensure equitable policies and practices for the pandemic response, including the Covid-19 Equity Taskforce and the Southeast Community Rapid Response Covid-19 Task Force.

But when it comes to the vaccine, spiritual leader Muhammad said he couldn’t in good conscience recommend it to his fellow residents.

“I have a responsibility as a Minister’s representative to share what we see through my lens: through the science, history, and scripture,” Muhammad said. “We are taught if we do not learn from history, we are doomed to repeat it.”

“We are standing firm against COVID-19. We just have concerns as far as it goes in terms of the vaccine. I will not take it.”

- Student Minister Abdul Waliullah Muhammad

Muhammad said his concerns about the vaccine’s safety are rooted in U.S. history and the present moment. Specifically, when vaccine producers Moderna and Pfizer asked congress for protection against litigation if the vaccines cause future death or injuries.

In fact, under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness or PREP Act, both Pfizer and Moderna were indeed granted “immunity from liability” if something unintentionally goes wrong with their vaccines. Muhammad said that he would wait to get vaccinated because of this and the country’s history of racism in medical research.

“I’m not yet convinced that this is safe at this point for our people,” Muhammad said, adding that his religious beliefs have taught him to be “a watchman for his people.”

Hood, the medical community at large, and the CDC affirm the vaccines for COVID-19 are effective and safe. Even though the pharmaceutical giants developed the vaccines faster than other vaccines in the past, the companies have assured the public the shots have been carefully tested.

Felicia House said she eventually overcame her fears, based in substantial part on Hood’s direction and facts from other physician leaders in southeast San Diego. She was recently vaccinated and is now trying to educate her community.

“I did get the vaccine, and I didn't, you know, turn into a zombie or anything,” House said with a smile. “I guess you could call me a ‘trusted messenger.’”

“Now, when I talk to my community, it's authentic,” she explained. “I can tell them I got the vaccine, and the most that I had [side-effect-wise] was a sore arm.”

Together, House, Hood, and other groups like the NAACP have created the website “Black COVID Facts SD,” where experts lay out the data and findings behind the COVID-19 vaccines and information on case rates among San Diego’s Black community.

House said hesitation to trust the vaccine is rampant, and the only cure to the problem is to put “facts over fear.”

“When you put the facts to the fear, then your mindset changes,” House said. “And remember everything is a mindset, so when you put the facts up against your fear, then you're able to overcome the fear.”

To learn more about how eligible patients can schedule a vaccine appointment in San Diego County, click here.