Nicholas Hoskins raced through a lot of emotions moments before a San Diego Police officer shattered his passenger-side window last month: Anger, frustration, and a sense that police were treating him differently because he’s Black. It was the fourth time he’d been stopped in just a year.

“It’s kind of demeaning. Emasculating. Sometimes I feel like I’m not a man,” Hoskins said. “I get irritated when I think about it a lot. Because y'all just violate me and do whatever you guys want.”

Hoskins’ experience doesn’t appear to be an outlier according to police stop data published by the San Diego Police Department. It’s data they have to publish because of a 2015 state law that aims to find out what role race plays during police stops.

That data showed racial disparities, statewide and locally in San Diego. More than half of the people stopped are Black and brown, even though most San Diegans are white.

NBC 7 Investigates looked at 666,406 police stops reported by San Diego Police over a 5-year period, from 2019 to 2023. Of that, people perceived as Black made up 22.5% of stops. According to the U.S. Census, only 6% of San Diegans are Black.

In comparison, Hispanic people accounted for 35% of stops compared with their share in the city’s population, which was only 30%.

Nearly half, 46%, of people stopped by San Diego police were white. But white people represent a larger share of the city’s population at 54.5% However, police and law enforcement experts don’t think that data tells the whole story.

San Diego Police Captain Jeffrey Jordon acknowledged the disparity but said the root cause of that is complex.

“Disparities, to be really clear, is a difference in how communities experience policing,” Jordon said. “The studies that have been done are not associated necessarily with bias, racism, discrimination. They focus on disparities.”

Jordon told us there are four different categories that play a role in the disparity. The department has some sway with three of them: where officers patrol, policies about when to stop and search someone, and officer explicit or implicit bias. However, there’s not much Jordon told us the department can do about the fourth factor driving the racial gap —poverty and crime.

While it’s true only about 6% of San Diegans are Black, Jordon says Black people make up about 15-20% of crime victims, and 25-30% of suspects, including 20% of 911 calls that lead to a traffic stop.

“And I want to be clear about this. You know, reducing disparities is not the sole governance of the police department in this city. There’s a lot of other players that are involved in this,” Jordon said. “Again, we’re going to police the way that we’re directed. The way our community directs us. The way elected officials are directing us.”

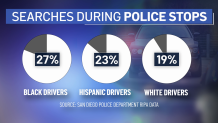

People of color more likely to be searched during stops

Black San Diegans were not only more likely to be stopped, they were also more likely to get searched, according to SDPD stop data. Nearly 30 percent (27%) of Black people pulled over during traffic stops have their vehicles searched. When police stop Hispanic people, officers search them 23% of the time. White people were only searched 19% of the time during traffic stops.

Despite these numbers, San Diego police officers were almost equally likely to find anything illegal, regardless of race. That could include guns, drugs, alcohol, or stolen property. On average, officers only find something 25% of the time they conduct a search.

Jordon says most searches are outside of an officer’s control.

“When we look at the reasons for searches, less than 10% are because of consent searches,” Jordon said. “It’s a very small proportion of how searches are conducted in the city of San Diego. People don’t necessarily realize, but about 90% of all our searches within the city of San Diego are dictated by policies and procedures.”

The vast majority of the time, Jordon says officers are obligated to perform a search because someone has a warrant for arrest, is on probation or parole, or because officers see drugs, alcohol or weapons. He adds another common reason officers conduct a search is probable cause — a reasonable belief the person either committed a crime or has evidence.

Leaving his past behind

It’s an understatement to say Hoskins doesn’t have the best history with police or our criminal justice system. Until recently, his entire life existed behind the razor-wire fences and metal bars of a California prison.

In 2014, prosecutors charged him and 16 other young adults with conspiracy, connected to a string of murders and attempted murders. Police believed the crimes were gang-related and that Hoskins was involved, something he has consistently denied. He says gang association is a label applied to anyone living in certain communities, like his own in Southeast San Diego. He says he was one of many who posted photos of themselves online throwing up gang signs to look cool or get girls.

“Everybody did it. Almost every house party,” Hoskins said. “I was a stupid, stupid teenager is all I can say. I was an ignorant stupid teenager.”

With no direct evidence tying him to the murders, prosecutors relied heavily on his Facebook posts, which they say celebrated the murders. He says he was just posting rap lyrics.

“I regret it too, because back then I wrote something stupid on Facebook every day,” Hoskins told us.

In the end, a jury convicted Hoskins of conspiracy to commit murder. The next eight years in prison were almost more than he could bear.

“It was hell,” Hoskins said. “I thought the world was over. I attempted suicide a couple times. It was a dark time in my life.”

That dark time ended last year when the California Supreme Court overturned his conviction. The justices ruled unanimously there was no evidence he ever committed or participated in any act of violence.

“It felt unbelievable,” Hoskins said. “I just kept reading the paper over and over again, pacing in my cell.”

San Diego County District Attorney Summer Stephan chose not to charge Hoskins again. He walked out of prison in February 2023. But free man or not. When he’s behind the wheel, he says his skin is the wrong color. He shared videos he recorded of his interactions with police with NBC 7 Investigates.

The flashing lights in Nicholas Hoskins’ rear-view mirror

The first happened just two months after leaving prison behind. Police stopped his cousin minutes after he picked Hoskins up from work in the East Village. He says the two were sitting in the parked car when police pulled up behind them and started asking questions.

His cousin, who’s on parole, was handcuffed. As a condition of parole, suspects waive their 4th amendment rights against unwarranted searches. They must instantly comply with searches of themselves, their cars, or their homes. And that’s what happened here. Afterward, both Hoskins and his cousin were released without charges.

Weeks later, Hoskins says police stopped him for a taped-up tail light. He says officers asked to search his car, but he said no, and they let him go without a citation.

This past March, San Diego police stopped Hoskins a third time. The officer told him his window tint was too dark, though didn’t write up a ticket. Instead, the officer asked him where he lived, if he had a job, his plans for the rest of the day, his phone number and social security number, and pointed out a speaker in the backseat looked expensive.

But it’s what happened during a 4th traffic stop, just last month, that drove Hoskins to speak out. He says he’d just left Southcrest Park and was on the way to pick up his son from a school bus stop. This time, when the officer walked up to his window, he said Hoskins didn’t come to a full stop at a stop sign.

After a series of questions, the officer asked Hoskins to step out of the car.

Officer: “Alright, go ahead and undo your seatbelt. I’m going to have you get out. Just make sure there’s no weapons..”

Hoskins: “No, I’m not about to get out the car…”

Officer: “I’m going to tell you what’s going to happen. OK? You’re going to take your seatbelt off. You’re going to put your wallet in the center console.”

Hoskins: “You guys…can I have my ID back and can you call your supervisor?”

Officer: “I’m telling you what’s going to happen, OK.”

Hoskins: “I have 15 minutes to go get my son. He’s getting dropped off at the bus stop at 4:30.”

Officer: “Nicholas, I’m going to open the door, you’re going to undo your seatbelt for me. OK? You’re an adult, I want you to go with the program here. I don’t want to have to…”

Hoskins: “What is the probable cause for a search?”

Officer: “Unlock the door for me.”

Hoskins: “What is the probable cause for a search?”

Officer: “Nicholas, unlock the car.”

Hoskins: “What is the probable cause for a search?”

Over the next two minutes, Hoskins continually told police he didn’t have any weapons. He asked for them to write him a ticket for the stop sign violation and refused to step out of his car for a search. Before a supervisor could arrive, the officer opted to smash the passenger-side window.

Officer: “This doesn’t need to happen man.”

Hoskins: “It doesn’t need to happen, you guys don’t need to search me. I’m about to go pick up my son. I’m a law-abiding citizen. I’m a tax-paying citizen. I’m not on paperwork or parole. I’m not doing anything wrong.”

Officer: “OK, I’m breaking your window.”

Officers handcuffed Hoskins and ultimately drove him to the police station downtown before releasing him. After searching his car, police gave him a ticket for resisting arrest. Hoskins says it cost him about a thousand dollars to get his car back from impound and replace the smashed window, which doesn’t really work.

“I think it’s wrong,” said San Diego criminal defense attorney Dante Pride. “I think what happened to that man is absolutely wrong. There was no reason to even take that that far.”

Pride says he gets calls from people who claim they experienced similar interactions every month — an experience he says affects those searched negatively for far longer than the duration of the stop.

“How many times have you been pulled out of your car for a traffic ticket?” asked Pride. “When you have somewhere to go and suddenly you’re stopped by police and asked to get out of the car, and you're treated like a criminal, you might be handcuffed, sat on the side of the road, cars are driving by looking at you. These are things that impact your psyche, your personality, your feelings for the day.”

Pride said police can’t explain away a consistent pattern without acknowledging what he believes is the biggest factor behind the racial gap in police stops — bias in policing strategies and personnel.

“Calling an officer a racist, or saying all cops are racist I agree is a conversation ender,” Pride said. “Nobody wants to hear, ‘Oh you're a racist.’ But if we can talk about biases and we can admit that we all have them and it doesn't make us a bad person for having them, then I think we can deal with the issue. But we have to have that conversation first.”

Also, Pride rejects the rationale often touted by law enforcement advocates that officers are more likely to pull over Black drivers because officers conduct more frequent patrols in crime-dense neighborhoods.

“When you look at the data, doesn’t make sense,” Pride said. “The criminal activity they’re targeting is not fully stopping at a stop sign. That happens as much in southeast San Diego as in La Jolla and there are not the same number of pullovers.”

SDPD’s data breaks down where stops occur, according to police beat. Those beat areas are roughly the same as neighborhoods. No neighborhoods saw more stops over the last five years than East Village, Pacific Beach, Midway, San Ysidro, and Ocean Beach. Generally, the number of police stops matches the population density of those areas.

A desire for more data

NBC 7 Investigates spoke at length with Paul Cappitelli, who says he made thousands of police stops during his 29 years with the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department. He also spent five years as the Executive Director of the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training (POST).

Cappitelli told us many of the questions officers ask during police stops may seem obtrusive, but serve an important purpose.

“You want to make sure they have a legitimate reason for being in that area at that moment,” Cappitelli said. “Nothing is ever, ever, ever good if it’s served to harass. We don’t ever want to see that.”

Cappitelli told us he takes serious issue with how the state looks at police stop data. He says it doesn’t include enough information about other factors that play into an officer’s decision to pull someone over or search their car.

“Data is just data. It’s numbers. It’s just the number, the stop, the stop, the stop. But it’s not what happened on the stop,” Cappitelli said. “As a former police officer who made literally thousands of traffic stops in my life I can tell you I did not start my shift and say, ‘Tonight, I’m going to stop X number of people of this race or X number of people of that race.’”

Cappitelli told us he’d like to see data collection expanded to include details about which officers are involved.

“I’m not going to stand here and tell you that there aren’t bad cops,” Cappitelli said. “I’m not gonna stand here and tell you that there are probably never any racist cops within the ranks of policing.”

But he believes any city’s demographic makeup will never match the demographics of who its police force stops.

“Policing will never be perfect,” Cappitelli said. “The whole comparative analysis of traffic stops versus the population will never ever be in sync. Because there’s always going to be too many variables involved.”

“I think the solution to a lot of these problems is officer discretion,” Pride said. “Inextricably intertwined with officer discretion is officer bias.”

Pride wants limitations on who police can pull over. For example, several other cities have restricted police from making traffic stops for vehicle infractions or limited pretextual stops.

Jordon pushes back on limiting police stops but agrees the answer to closing the racial gap will ultimately come from the community, and how the public wants to be policed.

“Ultimately, we’re going to have to have a conversation and this is one that’s not going to go away.”

Already Jordon says the department has cut down on the total number of police stops in an effort to address racial disparities. That was easy to see in the data; the number of stops decreased over the past five years. In 2019, there were nearly 188,000. But last year, that number was almost half of that at just over 102,000.

Taking action after a stop is over

Jordon, Pride and Cappitelli agree on several points, including what people should do when they are pulled over and asked to step out of their cars.

“This is going to be the worst thing I can say but unfortunately you just have to comply,” Pride said. “That is what you should do in that situation.”

“I don’t think it’s a good idea to refuse,” Cappitelli said. “You’re better off if you don’t think the officer is right, just let them do it and in the end, it’s all gonna flush out.”

Pride told us if you find yourself stopped by police and subjected to a search you don’t consent to, the best thing you can do is to record video with your phone. He says the time to fight mistreatment by police is not on the side of the road, but in front of a judge.

That’s exactly what Hoskins intends to do. He’s already filed a complaint with San Diego Police and hired an attorney with plans to sue the department.

“Just like they hold me accountable, I want them to be accountable,” Hoskins said. “They should be the examples.”

Hoskins starts trade school this month, hoping he’ll be able to find work as a carpenter or welder.

San Diego Police confirmed the stop is being reviewed as an internal affairs investigation, but would not comment directly on the incident.

How to report police misconduct

There are a variety of ways people can report alleged police misconduct. If it involves the San Diego Police Department, you can file a complaint directly with the department’s internal affairs division. You can also file a complaint with the Commission on Police Practices. That’s an independent community oversight body that has the power to make factual determinations and make recommendations about officers and policies.

If an incident involves the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department, you can file a complaint directly with the department. San Diego County also has a Citizens’ Law Enforcement Review Board where complaints can be filed.

J.W. August contributed to this report.