These days, the San Diego Police Department finds it’s responding to more than just emergencies in local communities. It’s also facing a real problem within its own ranks: Officers are leaving the force in near-record numbers.

With about three months to go this fiscal year, a total of 189 officers have left SDPD, about 20 per month, which, in total, is more than each of the last three full fiscal years.

Jared Wilson, president of the San Diego Police Officers Association, had very little positive to share about the situation.

“I would not recommend this agency right now," Wilson said. “I would not do that. The police department is broken and we need to fix it.”

Wilson said the exodus isn’t the result of one issue but said the vaccine mandate imposed by the city of San Diego pushed some over the edge, paving the way for others to follow.

“They told us they would leave, and they did” Wilson said. “And we told everyone that would happen last year.”

Last year, a police union survey showed more than 400 officers would consider quitting if the city enforced a vaccine mandate. The city said that so far, only 68 officers stated the mandate is the reason why they left, but Wilson feels the real number is much higher.

“It’s somewhat of a snowball,” Wilson told NBC 7. ”Once a few people leave, it just keeps going and going and going. And it’s just beyond the mandate at this point. It’s a catalyst but it’s not the main issue.”

The main issue, Wilson said, has been building for decades: low morale due to sub-average salaries. NBC 7 Investigates sat down with San Diego Mayor Todd Gloria, who acknowledged the issues facing the department.

“When I talk to police officers, I know they have a tough job,” Gloria said. “I know that we’re asking a tremendous amount out of them.”

Wilson told NBC 7 the police department is “broken.” The mayor disagrees.

“I want to be really clear: I think we have an incredible police department,” Gloria said. “We have a nearly 2,000-person police department of sworn officers that go out and do incredible work, and that’s reflected in the fact that we’re one of the safest big cities in the country.”

Gloria said that previous mayors and councils didn’t pay officers enough.

“We had a period in time where wage increases were not provided for nearly half a decade,” Gloria said. “We’re still paying the price today.”

The mayor pointed out that officers still received their planned 3% raise last year despite a budget deficit. This year, he said, he hopes to raise wages by even more and hopes to sign a new contract with the police before the city adopts a new budget, which he’ll propose on Friday.

“I have my work cut out for me," the mayor said. “But this is necessary. It's important. You saw that reflected in a tough budget year. You’ll continue to see that priority as the budget improves.”

Wilson said it’s not just pay. He says there’s a perceived lack of support from top city brass.

“It’s not one thing," Wilson said. “It’s a multitude of things.”

Wilson said the strain of losing officers for any reason is driving already-overworked officers to resign. The result, according to Wilson, is a thinner police force that’s less safe for both officers and the public it serves.

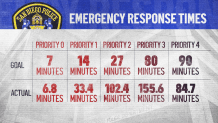

“When you're getting beat up on the street, and it takes 33 minutes for a police officer to get to you, that is unacceptable.”

He’s referencing the city’s annual performance reports for all its departments. It shows that last fiscal year, it took officers an average of 33.4 minutes to respond to Priority One calls. The target is less than half that: 14 minutes. The SDPD defines priority one calls as "… serious crimes in progress or a threat to life. Examples include: missing children, child abuse, domestic violence, disturbances involving weapons/violence and bomb threats." They aren’t as serious as emergency calls, of which the department met its time goal of seven minutes.

The mayor disagrees with the notion that staffing issues are driving down response times. He blames something else entirely.

“Here’s the thing: When you look at staffing levels, we have just shy of 1,900 officers at the city of San Diego.” Gloria said. “This is more officers than we had in 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020. That’s a good thing. To the extent that we’re challenged in this space is largely due to the fact that we see rising levels of crime that are reflected across the nation.”

Gloria also said the last three police academies were full. Making sure that happens is the daily mission of San Diego Police Department Lt. Steve Waldheim.

“The bottom line is that this is a great agency to work for,” Waldheim said.

Waldheim leads the department’s efforts on backgrounding and recruiting. He feels the effects of recent departures.

“It has a large impact in the fact that there’s more pressure for us,” Waldheim said. “We want to backfill these because we want to keep the city safe.”

Waldheim said the department is working to bring back an incentive program to attract transfers from other agencies, as well as bonuses for officers who recruit new hires. They also hope to sign a larger contract with a digital marketing agency, a contract SDPD lost to financial cuts during COVID.

“It was a big hit to us when we lost them,” Waldheim explained.

The lieutenant also said the department is going to more hiring expos and hopes to soon produce a recruiting video with a YouTube influencer.

The number of SDPD applicants increased in 2019 and 2020 but nosedived in 2021, dropping by nearly a thousand applications, down to 2,743 from 3,664 applicants.

The city of San Diego isn’t alone in facing staffing challenges. This past January, the Police Executive Research Forum surveyed nearly 200 departments. There were 23.6% more retirements in 2021 than in 2019, and 42.7% percent more resignations.

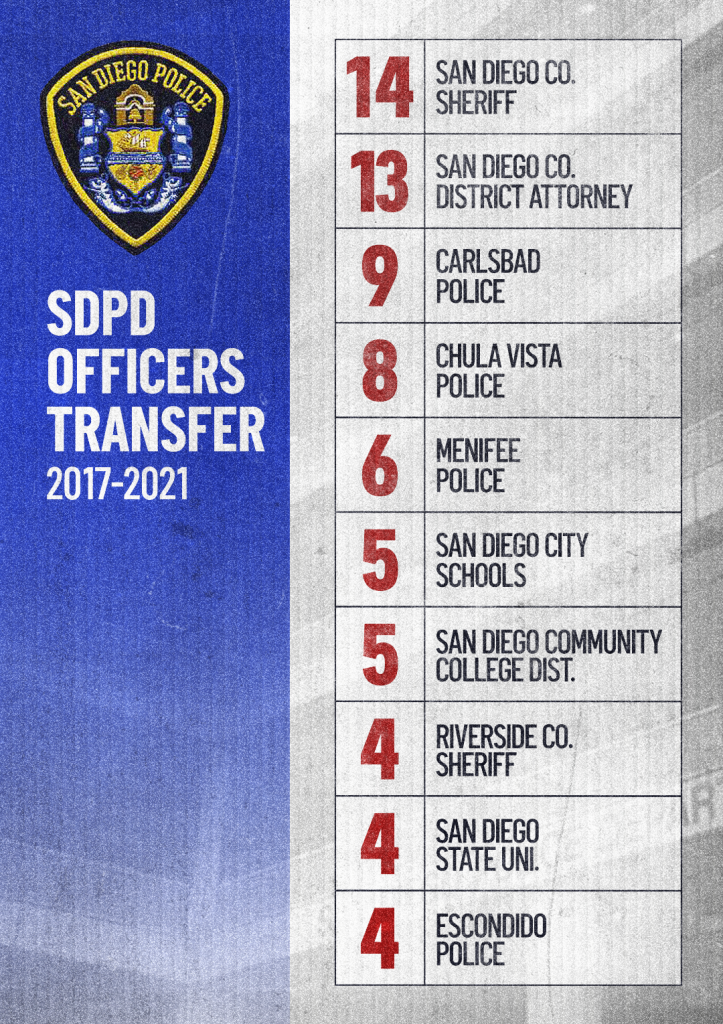

NBC 7 Investigates reviewed data for the entire state of California, showing where sworn officers work, and when. Over the past five full calendar years, 130 San Diego police officers left the city's force but stayed in state. Most went to the San Diego County Sheriff's Department.

David Leonhardi, the president of the Deputy Sheriffs’ Association of San Diego County, advocates for workers of the largest law enforcement agency in the county.

“We’re the varsity team of law enforcement in San Diego County,” Leonhardi said.

But, he said, even a “varsity team” will struggle if people don’t want to play the sport.

“We are hiring people today that might not be the best fit for law enforcement,” Leonhardi told us. “The reality is there are some minor calls for service that we don’t respond to anymore.”

Even the department most likely to be a destination for an SDPD transfer said it's losing deputies faster than they can be replaced. NBC 7 Investigates found that 254 deputies left the department last year, 49 more deputies than in 2020 and 82 more than in 2019.

“It’s not easy to stand in a line, have people call you hurtful names, call you things, throw rocks and bottles at you, injure you, when you’re literally just doing your job,” Leonhardi said. “That takes an emotional toll on people, an emotional and physical toll.”

After the sheriff’s department, San Diego Police officers were more likely to transfer to the County District Attorney’s Office, or the Carlsbad or Chula Vista police departments. (However, five of the 130 officers who left SDPD over the past five calendar years have since returned to the department.)

Chula Vista Police Chief Roxana Kennedy said the transfers have strengthened her department.

“So, that’s my job as a chief: to try to figure out the right person to be here with Chula Vista PD, long term,” Kennedy said. "That’s my goal.”

Kennedy took NBC 7 Investigates for an impromptu tour around the station after an interview, during which, it became quickly apparent, she knew everyone by name and every department.

Numbers show that CVPD is hiring and keeping officers at a time when many are handing in their badges elsewhere.

“When they look to Chula Vista, they look at us for family atmosphere,” Kennedy said. “They look at us for innovation because we’re very well known with our drone program.”

The Chula Vista Police Department is significantly smaller than SDPD or the county sheriff’s department. To prevent burnout, Kennedy said, the department invests heavily in tech.

“Chula Vista is the lowest staffed agency in San Diego County,” Kennedy said. “So the fact that we utilize technology — not to replace our officers but to enhance — has helped us tremendously … with how we’ve addressed crime in our community.”

Chula Vista also stands out in the salary department. The range for a peace officer in the South Bay city is $84,341 to $112,887. Compare that with SDPD, which has a salary range of $71,614 to $102,170. And almost unheard of at other agencies, in Chula Vista, officers get to pick their days off and their work shifts.

“I’m just proud of the atmosphere we’ve created here," Kennedy said. "I’m more than proud of the relationship with the community, this is a great place to work. I think that feeling valued and supported is really important in law enforcement, and I know that we feel that from our community.”