What to Know

- San Francisco has a growing number of art installations made with neon, LEDs and other light-emitting media

- SF Travel says interest in light-based art surged after the 2013 unveiling of The Bay Lights on the western span of the Bay Bridge

- Much of the artwork on SF Travel's self-guided tour is freely visible from public streets

Although it's a growing phenomenon in San Francisco, it would be easy to argue that using light as a medium for artwork is nothing new.

"Everything we do as artists is about these two holes," said artist Karina Smigla-Bobinski, pointing to the pupils of her eyes.

Smigla-Bobinski came to San Francisco from Munich to unveil her latest interactive work, "Kaleidoscope," now on display as part of the Exploratorium's seasonal light-based art exhibition called "Glow." It's the second stop on SF Travel's "Illuminate SF" light art trail, a part of the agency's annual festival promoting artwork that lights up.

"We decided about seven years ago to start a light art festival … during the darkest part of the year," said Brenda Tucker, SF Travel's arts marketing director.

Tucker said she's seen interest in light-based artwork rise since the 2013 unveiling of The Bay Lights, Leo Villareal's illuminated sculpture on the western span of the Bay Bridge.

The festival launched on Thanksgiving and runs through the first week in January, and features some seasonal pieces such as the ones at the Exploratorium, along with some newer permanent art installations. Most are free to view from public thoroughfares.

Included on the light art trail is a stop by Love Over Rules, a positively giant neon installation on an otherwise-blank wall that casts its glow over a busy downtown block of Mission Street.

California

Tucker said it's the first large public installation by artist Hank Willis Thomas — a message of peace that has a violent backstory.

"He was inspired by his cousin, who tragically was murdered through gun violence," Tucker said. "These are the last words that his cousin spoke to him on his voicemail."

The neon words cycle on and off in different patterns, changing their phrasing and thereby their meaning.

"It's a narrative style that can really say so many different things," Tucker said.

A completely different take on giant glowing capital letters, "White Light" by Jenny Holzer occupies a prime spot above the grand hall of the Salesforce Transit Center. Visible from below, above and behind, the flashing matrix of LEDs is at once an abstract work and a very concrete one — displaying whimsical patterns, but also scrolling excerpts from the work of more than 40 authors, most of whom had connections to the Bay Area.

"Not surprisingly, a lot of the artists have written about fog," said Jill Manton, director of the public art trust for the San Francisco Arts Commission.

Manton said the work is site-specific to the Transit Center: the speed and content of the scrolling text (which she had to read and approve in its entirety) is optimized for commuters who may be waiting for a bus — or, one day, a high speed train. With more than 30 hours of literary content displayed along the work's rippling glass surface, daily travelers who always board the same bus at the same time will be treated to a different piece of reading material every day.

Another celebration of the written word, "W.F.T" is a brand new permanent art installation on the side of the Bill Graham Civic Auditorium.

"It's entitled W.F.T, not W.T.F," Manton carefully clarified. "You know, everyone gets confused."

The letters stand for "Word Family Tree," and indeed, the work explores deep into the etymology of the words "Civic Auditorium."

"The etymology of those words actually coincided with historic events that had happened in Civic Center Plaza," Manton said. "Such as the legalization of gay marriage, and lo and behold we found out that one of the derivatives of the word 'civic' is the word 'marriage.'"

Artist Joseph Kosuth, who Manton said works only with neon components fabricated outside of Venice, Italy, had to wade through a veritable ocean of red tape to poke holes in a 100-year-old city building. All conduits and transformers had to remain on the outside of the building, and no architectural features could be changed in any way. A city-sanctioned electrical contractor had to handle the wiring.

While neon is a "traditional" medium as light-based artwork goes, there's nothing traditional about how the work was paid for: The owners of the new buildings across the street, who were required by law to contribute to public art as part of their building permit, gave the money to the city in exchange for beautifying the building their tenants will look at every day.

"It's made this facade of the building a highlight, an asset, a destination — as opposed to a blight," Manton said.

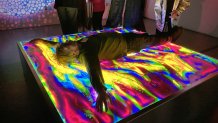

Artist Karina Smigla-Bobinski unveiled “Kaleidoscope” at the Exploratorium during an event where guests were invited to put their hands — and feet — all over the interactive sculpture. - Spherical Image - RICOH THETA

That brings us back to the Exploratorium, where a flurry of brightly-colored lights welcome visitors during the winter holiday season — but perhaps none as unusual as the glowing box called "Kaleidoscope" by Smigla-Bobinski, which appears to have every color of the rainbow oozing through it in rivers of translucent ink.

"You see this very huge lightbox with this crazy color on it," Smigla-Bobinski explained. "But there are only three colors on this lightbox, in the layers — and this is cyan, magenta and yellow. And I don't know if you know, but these colors we cannot see. These colors are produced completely by our brain."

With a recent social media explosion of articles explaining why the color magenta is just a figment of our imaginations (it doesn't exist in the spectrum of visible light), the timing couldn't be more perfect — and neither could the location. The Exploratorium is, after all, a hands-on discovery museum, and "Kaleidoscope" is meant to have visitors' hands — and even feet — all over it.

"I work all the time to try to develop works that are interactive and (don't) exist without visitors," Smigla-Bobinski said. "So everybody (is) invited to be part of my work, and to complete the work."

The three printing inks used in "Kaleidoscope" are separated by thin layers of plastic, so they splash around and form different colors as visitors play with them, but never actually mix.

"The mixing happens in your eyes," Smigla-Bobinski explained. "So by playing with this kaleidoscope, you are in fact playing with your own brain."