Women Hit Their Peak Earning Years in Their 40s: What Does That Mean for Millennials Sidetracked by the Pandemic?

As millennials begin to turn 40 in 2021, CNBC Make It has launched Middle-Aged Millennials, a series exploring how the oldest members of this generation have grown into adulthood amidst the backdrop of the Great Recession and the Covid-19 pandemic, student loans, stagnant wages and rising costs of living.

When Wendy Niculescu and her family moved from California to Oregon in January 2020, the wife and mom of two had high hopes for how the year would pan out.

She had just quit her role at a fundraising consultancy corporation in Los Angeles because her husband landed a new job at a local college in Oregon. The plan was for Niculescu to relocate, get her 2-year-old and 5-year-old settled into new schools and then look for a new job. But the Covid-19 pandemic hit shortly after her family's move, closing many businesses and child-care centers in Oregon.

"Any sort of trajectory that I had laid out for myself and this transition for us as a family has gone out the window," Niculescu tells CNBC Make It. With many companies on a hiring freeze, Niculescu was hard-pressed to find a full-time job. Even if she landed a part-time one, she knew it wouldn't pay enough to cover the "astronomical" costs of child care once schools opened back up. Thankfully, she says, her husband has been able to keep his job throughout the pandemic.

Get top local stories in San Diego delivered to you every morning. Sign up for NBC San Diego's News Headlines newsletter.

Niculescu isn't the only millennial who has been impacted by the pandemic's economic fallout. In fact, 59% of older millennials — those born between 1981 and 1988 — say the pandemic has affected their income in some way, according to a recent survey conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of CNBC Make It. For older millennial women like Nicuelscu, who will be turning 40 this year, experts worry the pandemic will alter their long-term earning potential. According to PayScale, women hit their peak earning age at 44.

"Lost earnings at any juncture impacts the ability for women to save, to invest and to build their wealth," PayScale chief people officer Shelly Holt says. "So, when you think about that [older] millennial population, now is the time where they should be close to earning the most, [but] this pandemic has been really scary for women."

Money Report

Women have lost more than 4.6 million net jobs since February 2020, while men have lost nearly 3.8 million in that time period, according to the National Women's Law Center. Additionally, more than 1.8 million women have left the labor force since since then, meaning they are no longer looking for work. The labor force participation rate for women dropped to 57.4% in March, its lowest level since December 1988, NWLC says. The rate stood at 59.2% before the pandemic.

In contrast, men's labor force participation rate stood at 69.5% in March. That's still a drop from the 71.6% rate seen in February 2020.

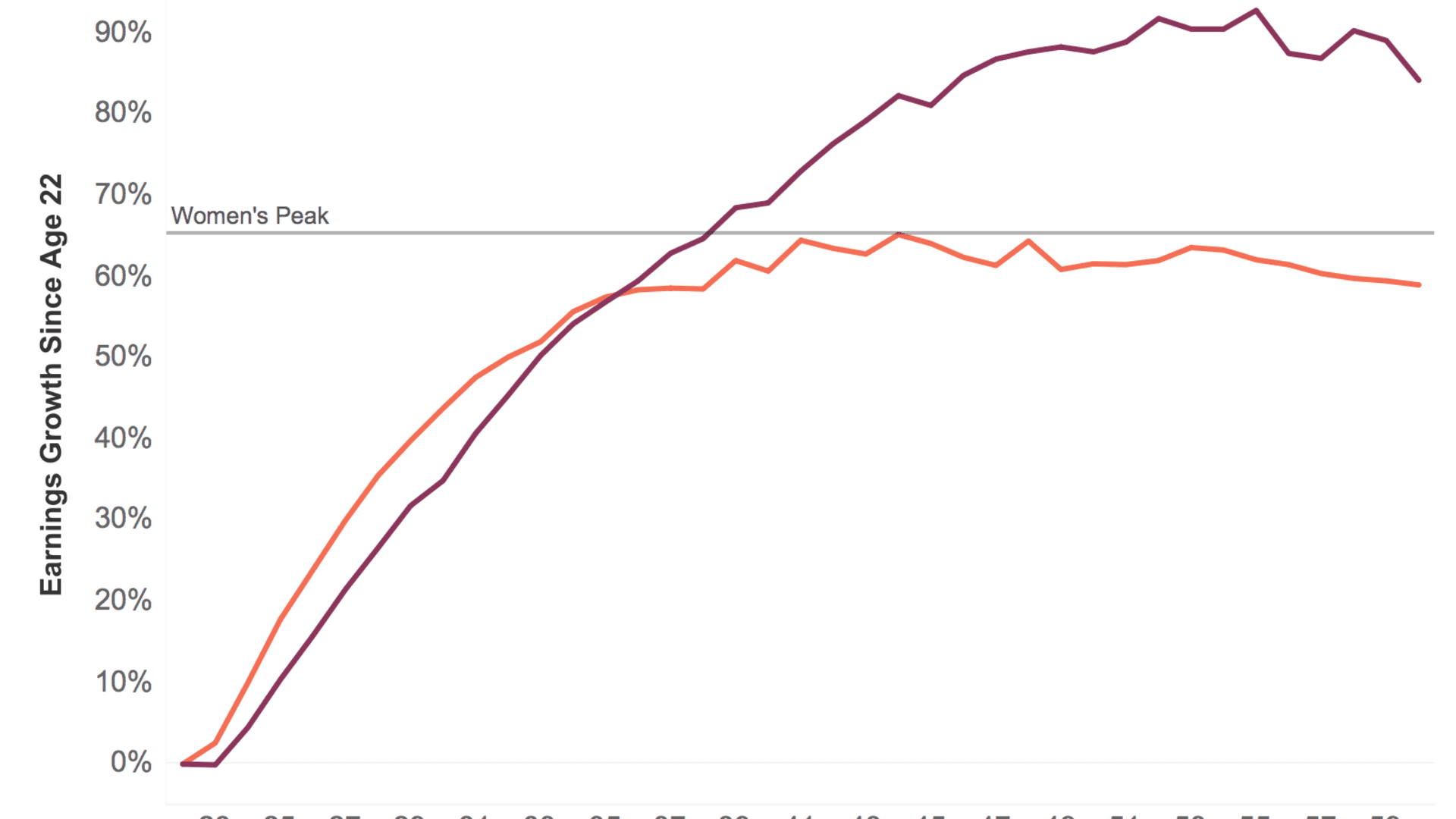

While many factors contribute to women being pushed out of the workplace by the pandemic, Holt says the "larger unemployment penalties" women have always faced play a huge role in this mass exit. They also contribute to women hitting their peak earning age at 44. For men, that age is 55.

The motherhood penalty and the fatherhood premium

One of the main penalties is the motherhood penalty, which often describes the career sacrifices women feel pressured to make when they start having children.

The average woman with at least a bachelor's degree enters the workforce making less than men as occupational choices and gender bias contributing this disparity, according to PayScale.

At age 22, the median yearly income for women with at least a bachelor's degree is $40,400, compared with $52,500 for men with the same age and educational background. This $12,100 wage gap starts to shrink as women's wages grow faster than men's throughout most of their 20s. Around age 29, women's wage growth starts to slow down while men's wages keep growing, PayScale data shows. As women hit their late 30s and early 40s, their wages start to flatline. At age 44, women reach their earning peak, making a median salary of $66,700 per year. Meanwhile, men continue to see their wages grow, hitting their peak earning age at 55, making a median wage of $101,200 per year.

"One of the main explanations for the earnings gap in the U.S. is the motherhood penalty," says Yana Rodgers, an economist and professor at Rutgers University. She explains that as women enter their 30s — and even early 40s — they "sometimes take more flexible jobs that pay less so that they can balance motherhood with their work." Some women decide to take a break from work completely in order to care for children or a family member.

In many cases, she says, "some discrimination is involved," where women are perceived to be less deserving of a promotion or less invested in their work if they need more flexibility to care for their family.

Rodgers emphasizes that because women are often expected to carry the brunt of child care and household responsibilities, many men benefit from a "fatherhood premium" where they're able to work the same amount of hours, or more, as they have kids. This premium — as explained in PayScale's report — allows men to move into high-paying, senior-level roles in the years when women often take a career break, thus leading women to hit their earning peak early because of a career interruption.

The pandemic, Rodgers and Holt explain, has only exacerbated this motherhood penalty. In September, one in four women in the workforce were thinking about downshifting their careers or leaving their jobs, according to a report from Lean In and McKinsey. One of the main reasons for this, the report says, is the ongoing caregiving crisis women face, which has been intensified by the pandemic a schools and day care centers being closed.

Mothers are three times as likely as fathers to be responsible for a majority of housework and child care during Covid-19, the report found. Mothers are also twice as likely as fathers to worry that their work performance is being judged negatively because of their caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic.

"Mothers were already working a double shift," Facebook Chief Operating Officer and Lean In founder Sheryl Sandberg says. "Now with coronavirus, what you have is a double double shift. You know, mothers are spending 20 more hours a week on housework and child care during coronavirus than fathers. Twenty more hours a week is half of a full-time job."

As schools reopen and the economy recovers, Rodgers says many women who are looking to reenter the workforce may earn less, further impacting their salary during their peak earning years. People who return to work after less than a year of unemployment typically make 4% less than someone who has not taken a career break, PayScale reports. Meanwhile, someone who has been unemployed for more than a year typically makes 7.3% less than someone who has remained employed.

"I do want to emphasize that this is no longer just a women's work issue," says Rodgers. "It's also a macroeconomic issue [that] has long-term repercussions for our country's GDP."

Increasing women's labor force participation rate, can boost GDP by over $6 trillion, according to UN Women.

The "messy middle"

In addition to the "motherhood penalty," Rodgers explains that the "messy middle" — or what Lean In and McKinsey call "the broken rung" — also impacts women's earning potential.

Rodgers says the concept refers to the "blind spot within corporations" where companies "do a pretty good job retaining women who come in at the entry level and they've gotten better in how they treat women in the very top leadership positions, but they're not advancing women who are in the middle of the totem pole." As a result, many women find themselves stagnant as they are overlooked for promotions, while many men are able to move up the corporate ladder at a much faster pace.

Only 85 women are promoted for every 100 men promoted to manager, according to Lean In and McKinsey & Company. This disparity is even larger for Black women and Latinas, with 58 and 71 women, respectively, being promoted for every 100 men. This gap in promotion correlates with the lack of female representation in high-paying C-suite jobs.

In 2020, white women made up 29% of the entry-level workforce and women of color made up 18%, according to Lean In and McKinsey. Yet, the number of women in C-suite roles dropped to 19% for white women and 3% for women of color.

This "stagnation helps explain why women reach their peak earning age 11 years before men, Rodgers says.

Solutions for addressing this gap

To address the pay gaps women face, Holt says equity should be "central to any company's approach to pay."

When looking at pay equity, she emphasizes that a "one-off pay equity event" or a single review session isn't enough. Instead, she says company leaders need to have pay equity reviews at all levels of the recruitment process to ensure that fairness is present at "every job offer, every promotion and at every merit increase cycle."

In addition to equity in pay and promotions, Rodgers says company leaders need to also stop "stigmatizing employees who are on the parental track, or what used to be called 'the mommy track.'"

"Employers, even the bosses themselves, need to offer and take advantage of things like flex time, job sharing, working from home, and other kinds of family friendly policies for both men and women," she says. "It used to be that people, especially women, were stigmatized for taking advantage of these policies." But now, with the pandemic making remote work "quite the norm" for many industries, she says she hopes employers will move past this stigma and allow women to comfortably take advantage of long-term flexible work options.

At the national level, Rodgers adds that "universally accessible, free child care, as well as long-term elder care" can also provide women with the support they need to stay in the workplace. She added that a national paid family leave policy should be mandated. The U.S. is one of the few countries in the world without one.

Niculescu — who hopes to land a job soon after being out of work for over a year — says affordable child care and workplace flexibility certainly benefit working mothers like herself. But, in addition to these resources, she says a real shift needs to take place around the traditional narrative of what women are responsible for and expected to do in the home.

"I have two young girls and watching what people expect them to behave like, or expect them to do, or even what I expect them to do because it's ingrained in me [for women] to be these nurturers, to be caretakers and to be extra responsible, you know it's unfair and it's costing women," she says.

CNBC Make It will be publishing more stories in the Middle-Aged Millennials series around student loans, employment, wealth, diversity and health. If you're an older millennial (ages 33 to 40), share your story with us for a chance to be featured in a future installment.

Check out: Meet the middle-aged millennial: Homeowner, debt-burdened and turning 40