Countless institutions are adapting to survive the pandemic -- and museums are no exception. An online article in Bloomberg.com this week reported museums are selling artworks to stay afloat -- and also to diversify their collections in the wake of the racial-justice movement.

"Springfield Museums in Massachusetts offloaded a Picasso for $4.4 million … [and] the Baltimore Museum of Art is shopping around its signature, monumental Last Supper by Andy Warhol for about $40 million," Bloomberg.com reported.

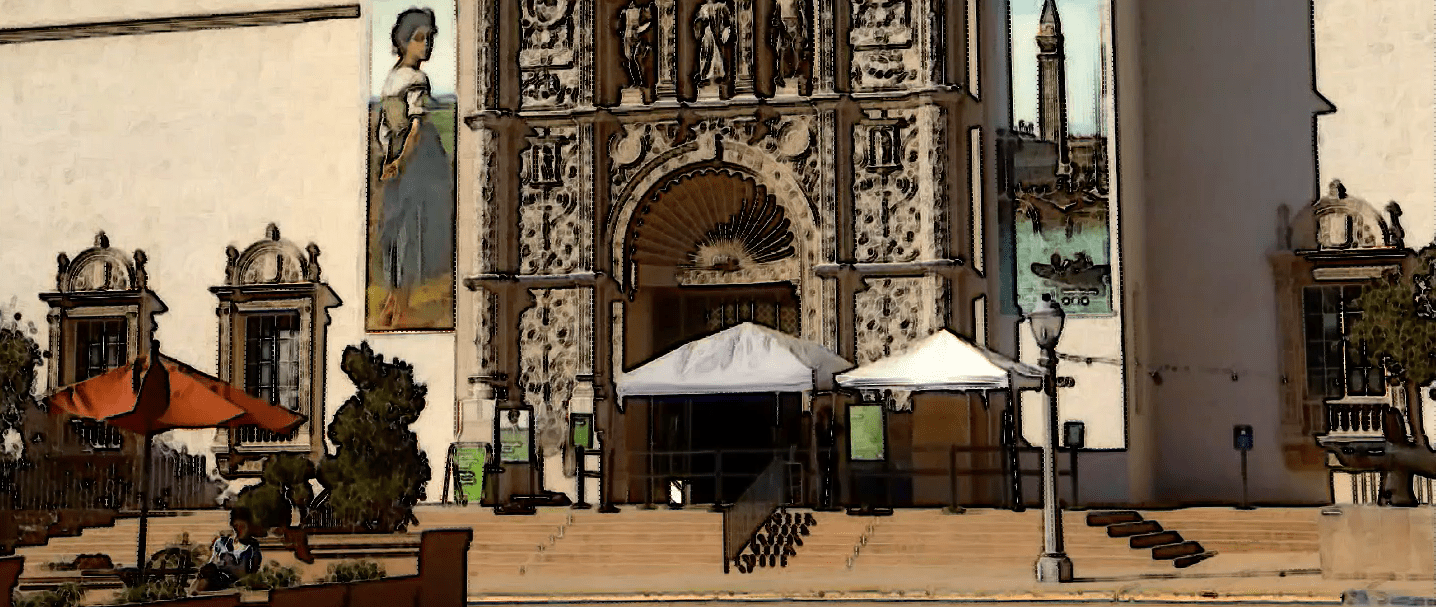

Also mentioned in the piece: the San Diego Museum of Art. On Wednesday, some pieces from its collection went up for auction at Sotheby's, including the sale's featured highlight, Bernardo Bellotto"s 18th-century "Architectural Capriccio." Auction estimates put the value of the painting between $700,000 and $900,000, but the reserve price was not met at the auction, and, as a result, the piece was unsold, a Sotheby's employee told NBC 7 on Thursday.

However, "An Interior With Three Children Playing With a Cat," by a follower of Jan Steen, fetched $3,780 at the sale, and "Moonlit River Landscape With Boats, Fisherman and Cows," by a follower of Aert Van Der Neer, sold for $2,772; both were offered without reserve.

Roxana Velásquez, the executive director of the San Diego Museum of Art, told NBC 7 this week that proceeds from the sales would be used to purchase new works that would enhance the permanent collection, and that such sales are normal for museums.

"The process is called deaccessioning," Velásquez said. "The museums, the art museums do that as a normal practice, and the purpose is to enhance the permanent collection. For this museum, the No. 1 goal in the strategic plan is the enhancement, the betterment, the refinement of the permanent collection. So we have been doing this for the last six years -- actively, six years -- and nine years ago we started with this process. It's a long process, but it's part of the strategic plan."

Velásquez said that as a museum with a so-called encyclopedic collection, diversification is built into its DNA but efforts at diversification would be part of the acquisition process once the proceeds from the auction sales are realized.

"We all want to improve our collections, diversify our collections," Velásquez said. "Of course we do this as a common practice. It has always been there … it's not random, it's not an emergency. So for the San Diego Museum of Art, it's part of our strategic plan, and it has been a pro-active move all the time."

Recent visitors to the museum may have been surprised that they often have a gallery to themselves. To a degree, of course, this is due to pandemic restrictions: Museums are currently only permitted to admit 25% of their maximum occupancy. Still, solo experiences like those give rise to questions about the Museum of Art's financial health.

"So we are back to 80% of capacity compared to last year, so 80% is an enormous number but it only speaks of the community, as I said, eager to visit their art," Velásquez said. "The first weekend that we opened, I have to report to you, we had 1,600 people visiting the museum [over two weekend days]."

Fortunately for San Diegans, national and local foundations and benefactors stepped up to help out during the museum's closure.

"We have a great group of supporters and trustees and members of the community and volunteers who have contributed and have always been there for us," Velásquez said. "But this institution … is doing financially well…. We did receive different grants from different foundations. Nationally speaking, I would mention to you the National Endowment for the Arts, the Terra Foundation, just to mention some, the Price Charities … and, of course, we also got gifts from individuals from the board who know that we do need extra help these days …"

Velásquez offered a window into the decision-making that goes into selecting which pieces the museum will sell, a process that includes conversations with other museums in the region.

"What is the object you are deaccessing, why are you doing it; what is the context, the relevance or the irrelevance of the object; and you check everything, meaning the provenance but also, is there somebody nearby in your city that would use this object?" Velásquez said. "For example, you offer it to your colleagues in town. Then, after you have covered all those processes, which means four of five committees, then you get to the public option … Sotheby's, Christie's, Bonhams, and that's the public domain."

The reality, though, is it's likely museum-goers have never even seen the pieces that are headed out the door.

"We do have two major galleries that are temporary exhibitions that have 9,000 square footage, so that allows us to change constantly, depending on the format or the size of the pieces, but it's between 2 to 3% of the collection that you are seeing right now in the galleries," Velásquez said.

While museum-goers may not recognize the artworks selected for sale, they would certainly recognize the name of at least one artist whose work the SDMart has parted with: In June, the museum auctioned off "a remarkable portrait by Pierre Auguste Renoir," according to the Sotheby's.com. The 1907 Renoir fetched $524,000.

When the art pieces from SDMA do come up for sale, they go home with the highest bidder, which could be a private collector but also be another museum elsewhere.