Genetic researchers studying variations in personalities may have answered an age-old question: Why are some people able to successfully navigate a cocktail party while others struggle to make the smallest of small talk?

While not able to apply their research to all party animals, the theory that researchers at UC San Diego's Sanford Stem Cell Institute are working on begins with a rare genetic condition called Williams syndrome, which is caused by the "deletion of about 25 genes in the 7q11.23 chromosomal region,' " according to a news release the university sent out, "and which is sometimes called 'the opposite of autism.' "

People with Williams are extremely social, chatty to a fault and sometimes have an oversize vocabulary that can hide what is normally perceived to be a below-average intelligence.

April is Autism Awareness Month

Get San Diego local news, weather forecasts, sports and lifestyle stories to your inbox. Sign up for NBC San Diego newsletters.

"They have, like, a low IQ," Alysson Muotri told NBC 7. "They have developmental delays, but the vocabulary is quite enriched and above the average for people of their age. And this is independent of cultures. People in Japan with Williams syndrome behave in the same way. So the genetic here is really strong."

Another major downside: Those who are missing the 25 genes, and, specifically, GTF2I, "know no strangers, making them particularly vulnerable to abuse and bullying," as the science folks put it in their release.

On the flip side of Williams, people who have a genetic duplication in the 7q11.23 chromosomal region — known as, not surprisingly, 7q11.23 duplication syndrome — may experience autism, social phobia or, in some cases, "selective mutism."

While Williams has been studied earlier and elsewhere, researchers at UC San Diego focused on that one gene in particular — GTF2I — which they theorized was controlling the variations in personality.

Muotri is the director of the UC San Diego's Sanford Stem Cell Education and Integrated Space Stem Cell Orbital Research Center and lead author of the paper. The gregarious Brazilian ex-pat professor, who has been in the San Diego area off and on since 2002, lives in PB and loves to surf and hike when he's not also acting as the school's director of the Archealization Center and its Gene Therapy Initiative, as well as the associate director for the Center for Academic Research & Training in Anthropogeny. The guy has a resume, for sure, and he's had an effect at UC San Diego. He said about 80% of the 35 or so people working in his lab are from Brazil.

“I like to describe this gene as the gene of prejudice,” Muotri said in the news release. “Without it, everyone in the world is your friend.”

Although researchers in the past have connected many genes to autism, GTF2I “is the only gene we are aware of that regulates socialization more directly,” according to Muotri.

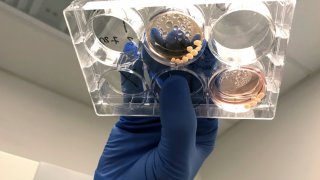

After the hypothesis evolved to the point it was ready to be tested, the UC San Diego lab grew "mini brains," as Muotri called them, from stem cells that would then imitate the development of a fetal brain, but one without the GTF2I gene. What researchers found was that in the absence of the gene, more cells died, there were defects in synapses and less electrical activity. All as bad as it sounds. On the other hand, genetic experiments with fruit flies yielded a surprising result.

"Fruit flies with the same alteration, genetic alteration, also become more social," Muotri told NBC 7 in a recent interview. "Usually, fruit flies prefer to eat very independently from each other, but fruit flies that [were] genetically engineered to carry this genetic alteration, they start having meals together."

Scientists are fond of fruit flies' relatively brief lifespans and simple physiological systems. With their genomes edited to include GTF2I, they eat "without the usually obligatory 'social bubble,' " and mice with the gene, are, well, friendlier, according to the UC San Diego researchers.

And then there's this bomb from the news release: "alterations to a gene that controls the function of GTF2I — potentially turning it off — may be at least partially responsible for the loving, friendly disposition of domesticated dogs compared to wild wolves." In other words, there might be no dogs if all canines had GTF2I.

"So this region in the chromosome is so important for sociability and very conserved in different species — we actually see that that region was affected during the domestication of dogs, from wolves to dogs," Muotri told NBC 7. "I mean, we see that they become more docile and they become more social. And the dogs, they even make very good eye contact compared to wolves. So this is definitely something that you see in other species."

One real-world application the research may be used for is treating people with autism.

"By studying this GTF2I gene, it allows us to dissect the molecular pathway that is inside the cells to create or to make your brain cells become highly social," Muotri told NBC 7. "By designing drugs that can modulate that pathway, we can use and apply to autism, inducing your brain to become more social."

Muotri said that design is being worked on now, in fact.

"Sometimes we team up with the pharmaceutical industry if there is a commercial interest," Muotri told NBC 7. "In the case of Williams syndrome, it's less obvious because this is a rare syndrome, but in this case, we are applying what we have learned from Williams syndrome to a more common condition: That's autism."

Muotri thinks that the GTF2I gene, or the lack thereof, could be a contributor to what distinguishes humans from their closest genetic cousin, chimpanzees, who are social animals, of course, but to much less of a degree.

"The chimpanzees, they have a social brain that is able to deal with about 15 individuals per colony, so when the colony that they live [in starts] to grow bigger, there is usually a crisis, or they start fighting, and some [of the apes] have to leave the colony," Muotri said. "We humans, we triple that social capability. So we can deal with 150 people at the same time, and we can even use hierarchical social interactions, meaning that I talk to you in a different way than I talk to the father of my wife, because I know the different hierarchy that goes to that. So the chimpanzees, they also have that, but in a less sophisticated way."

Muotri stressed that GTF2I is only one element of the equation.

"Remember, GTF2I is just one of the genes that are responsible for your social behavior," Muotri said. "There are other genes that act together with GT2I. This one is just interesting because it affects so directly how social you are that there is even what we call a polymorphism among humans, meaning that the difference in the levels of GTF2I in my brain and in your brain might be different. And depending on how much you have or I have, I'd be more or less social because of that."

This lack of GTF2I in human's brains may be profound, the professor theorized.

“It’s when we cooperate that we can put a man on the moon," Muotri said in the news release. "It’s when we cooperate that we can decode the human genome. Because we work together.”

While it seems like Planet of the Apes could be on the menu in the hands of a mad scientist, it's worth remembering that there are no dog cities. Planet of the Dogs?

Still, it's easy to follow this thread: If introducing the GTF2I gene into somebody with autism could ratchet up their level of sociability, could it have the same effect on a so-called "normal" person? Would it turn them into a social butterfly?

"You could, yeah, eventually you could," Muotri posited. "And by the way, there are drugs out there that people take to enhance their sociability. And I would say that one of the most used drugs in humanity is for that. And it's either alcohol or coffee."

But would this third option alter an average person so that they became more confident, more outgoing, have a better vocabulary?

"Well, it is a possibility that this might happen with normal people," Muotri told NBC 7. "Of course, it's not the intention of the research, but as a side-effect, it might well happen. This is what we are seeing now with some of the research in psychedelics. There are some of these psychedelic drugs that increase your serotonin level, and this is one of the neurotransmitters that makes you more social."

Roughly 1% of the population has some form of autism, according to Muotri, so a drug could have a huge pool of potential patients. It's not difficult to imagine a much larger market for people who might want to seem smarter and more confident in social settings. Still, it's not something Muotri and his lab is pursuing.

"I have not proposed that [to the pharmaceutical companies]," Muotri said. "The first thing that we need to know is if the drug has side-effects, because nobody wants to increase your sociability if we start, let's say, vomiting, right away."

Want even more science? Click here to read the full study.