When Rhonda Connolly had her second son, Casey, she and her husband brought him back to their Del Mar home thinking everything was fine.

She was breastfeeding her seemingly healthy baby, not knowing every meal was putting protein into his body that turned into brain damage-causing toxins.

Three days after Casey’s birth, his pediatrician called saying his newborn screening test results were abnormal.

Their son tested positive for Phenylketonuria or PKU, a rare condition in which a baby is born without the ability to properly break down an amino acid called phenylalanine. If a person with PKU has too much protein, it builds up toxins that can cause permanent brain damage.

The Connolly family received the newborn screening results on time, and it was imperative they did. Doctors were able to treat Casey immediately.

However, in some hospitals around the country and in San Diego County, samples are taking longer than the recommended three to five days to reach a laboratory.

Federal health advisors and newborn screening advocates say the dangerous delays put babies in danger and their families at risk of having to deal with expensive, lifelong medical bills.

The California New Born Screening Program screens more than 98 percent of babies born in the state, according to the California Department of Public Health (CDPH). It tests for 31 conditions.

“The baby can look normal, but in a few days or after that may exhibit abnormal findings that can be associated with a serious neurological disability, developmental problems or even death,” said Dr. Joseph Bocchini the chairman of the Secretary Advisory Committee for HRSA on heritable disorders in newborns and children.

“There are some conditions that are severe that may manifest themselves in the first week of life. They can be fatal, critical conditions,” he said.

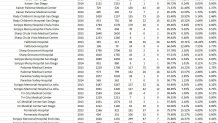

NBC 7 Investigates obtained CDPH information revealing 24 samples from Fallbrook Hospital in 2013 took more than five days.

At Rady Children’s Hospital, where babies are born elsewhere and transferred to its NICU, 35 samples in 2013 exceeded the time limit. Fifteen late tests have been recorded from Rady in 2014 so far.

For Scripps and Sharp hospitals, the percentages of delayed tests were very low, varying between 0 and .75 percent.

Jill Levy-Fish is the president of the Save Babies Through Screening Foundation. She said one delay is one too many.

“We’ve lost children and children have become impaired for the sheer fact samples have been delayed and there is no excuse for that,” she told NBC 7 Investigates.

All the hospitals NBC 7 reached out to declined on-camera interviews, but Fallbrook Hospital’s Marketing and PR Director Monique Murphy-Mijares released the following statement:

“Our hospital has processes in place, including use of overnight delivery services, to ensure that specimens are received by the state lab within the standard of five days or less after collection. Monday through Friday, our specimens are picked up within 24 hours, while specimens drawn over the weekend go out on Mondays. We monitor our results to ensure consistent processing and delivery on an ongoing basis. Everyone in our organization understands the sensitivity of these shipments and the important part we play in getting timely test results to parents.”

Rady Children’s Hospital Senior Public Information Officer Ben Metcalf also responded to the NBC 7 investigation by email, clarifying some of its numbers.

“These numbers reflect an improvement over the numbers in the Sentinel Journal report you referenced. Although the statistics have improved, we continue to look for ways to come as close to 100 percent as possible. Another fact to consider is that some of the samples that took more than 5 days were re-tests, meaning the initial sample was sent to the lab within the 5 day guideline, but had to be retested due to being an inadequate specimen. Rady Children’s has the only level 5 NICU in the region, so we care for the sickest babies. The nature of these samples can lead to higher numbers of inadequate specimens and therefore more re-tests.”

Rhonda Connolly’s son, Casey, is now 22 years old. He’s healthy, although dealing with PKU is a day-to-day struggle.

When Casey was eight years old, his mother had a third son they named Brady. Brady’s screening, which they also received on time, revealed he too had PKU.

“If it was your child being diagnosed with something, every day makes a difference,” Connolly said.